A Serendipitous Encounter with Art in the Writing of Art Criticism

Chien-hung Huang

1

In 2007, Yuki Okumura, an artist-in-residence in Taipei then, introduced the works by Koki Tanaka and Taro Izumi to me. Later in the same year, I flipped through Koki’s portfolio at the bookstore of the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, and I loved it too much to part with it. On the occasion of the 2008 Taipei Biennial, I first made Koki’s acquaintance via Manray Hsu. Then, in the same year, I visited Sun-Jung Kim’s curatorial project Platform Seoul in which Koki presented his installation in a detached house, an installation giving prominence to the head-on collisions among a couple of bulk-like objects, as if the memories of this space could be triggered through this ritual. Koki’s video art works thenceforth established a constant presence in my writings of art criticism. As I visited the BankART1929 in Yokohama in 2009, I saw the image of Koki’s work gracing the cover of the institution’s publication.

The image featured him sitting on a drifting raft he assembled in 2007 with the detritus of the institution’s exhibitions, from which I felt great visceral thrills despite the tranquil surroundings. Koki’s art projects dispelled the stereotype of dailiness as rigmarole. As far as I was concerned, his performances and video artworks were nothing short of the endogenous actions and images emitting sound within the temporal framework, enabling the dailiness to deviate from the route dictated by industrial time and practical utility. The sense of dailiness thus emerged as an event in our consciousness and living space at the call of the sound.

Title: I considered the title of this work but it never come up. Following things could be related to the title.

1) I love to go out from the exhibition space because of BankART facing the sea.

2)There are so many trashes which some artists made and showed as art work before in BankART.

3) I want to make a raft using those trashes.

4) I think it’s not a question that the raft oat on water or not but it’s good to be oating there. Year: 2007 Material: performance, project, raft Size: 14m for the raft View: Installation at La Chaine BankART Studio NYK, Yokohama

In 2015, I saw Koki’s site-specific work Provisional Studies at Parasophia: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture. This work was a quasi-workshop setting juxtaposed with its space, knowledge of history, mobile objects and project images, in which the sound of dailiness seemed to be replaced by the lingering voice from different directions. I can dimly recall that I felt cast adrift in a construction site, waiting for something to be rebuilt there when I stopped to gaze at this work. In 2016, I invited Koki to present his work at Discordant Harmony, an art project comprised of three exhibitions in three countries. The third exhibition took place in Taipei, focusing on the “way” in which individuals respond to the system. I was itching to display Koki’s work Provisional Studies: Workshop #1 – 1946–52 Occupation Era, and 1970 between Man and Matter in that exhibition. Employing a mise-en-abyme structure, this work delved deep into a subtle cultural dimension from the memories of the post-war U.S. military occupation via the history of the exhibition space, and meanwhile encouraged young visitors’ reflection on the past. I originally planned to extend this experiment to the discussion about the historical understandings possessed by people in the neighboring countries, only to be subject to some conditions and had no choice but to display the videos of Workshops #3 and #5 of Provisional Studies. With the wisdom of hindsight, I recognized my own shortcomings. More specific, I could see only part of the project within the narrow confines of the exhibition installation, without comprehending the holistic implication and development of the artist’s philosophy and practice.

Project title: Provisional Studies: Workshop #1 “1946–52 Occupation Era, and 1970 Between Man and Matter”

Date: December 6 – 7, 2014

Format: Action, workshop, and video documentation

Location: Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art

Video still, Koki Tanaka, Vulnerable Histories (A Road Movie) ,2018, Film, Action

In 2017, Hu Fang ushered me to a new phase of comprehending Koki Tanaka and his oeuvre. It was a research process inextricable from the place named Mirrored Gardens, starting from agronomy-based practice to the relations between the works and the space-time of the exhibitions, which would be inspired by the natural forest, as well as from grasping the works’ creative processes to the cogitation on moving images. At that time, Tarek Atoui’s project “The Ground” at the Mirrored Gardens came as a complete revelation to me. My habitual approach to images was thenceforth discarded in favor of “Umwelt” and “Grund” as the point of departure for contemplating creativity. This event substantially refreshed my understanding about Koki and his creative style after 2011. At the end of 2017, Koki Tanaka, Gabriel Ritter, Yung Ma and I gathered together in the Mirrored Gardens, engaging in a two-day intensive gathering “Encountering Moving Images in the Woods.” We not only had a better sense of Koki’s oeuvre, but also discovered the rheological interplay between image and discourse. By virtue of the openness and transparency of the organic environment and being prepared to share related information, we tried to communicate in a more relaxed and direct fashion, raising questions when viewing moving images and chewing over the essence of image via discussion. To put it another way, image, viewing and discourse penetrated one another, so that we could explore the possibilities of forging a closer relationship with image.

In 2018, Koki Tanaka staged his solo exhibition titled Vulnerable Histories (A Road Movie) at the Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst in Zürich. I was pleasantly surprised by this brilliant art project. Koki revolved the pertinent meetings, dialogues, courses, followup visits and gatherings around the subjects of migration and hybridity, and managed to weave the “refinement and profoundness of questions” by corresponding, dining, walking and having in-depth conversation with the two protagonists as well as listening respectfully to them. This project can be construed as an extension of Koki’s work How to Live Together presented at the Skulptur Projekte in Münster. However, on the part of gathering in this project, the “histories of the vulnerable” converged precisely on their indescribable, innermost secret, a physical awareness which I provisionally termed “para-colonial.” Skillfully manipulatingcorrespondences and cinematography, Koki gradually increased the profoundness of the concealed indescribability in the process of intimate exchange. Accordingly, the connection between cinematography and the highly para-colonial dailiness here did not refer to story-writing, sensory stimulation, or the temporal depth derived from the sublimity of “situation” (fixed shot) composed of an individual and the environment. Rather, it directly transformed the fractures among quotidian behavior, discourses and relations into the intervals among images. Besides, the “vulnerable consciousness” lodged in the protagonists became the steady accumulation of insistence by the proceeding of images, and the discursive practice manifested by the correspondences in turn replaced common image languages and narratives (consumeroriented design). Within a thoroughly cinematographic framework, Vulnerable Histories (A Road Movie) restructured an alternative “dynamism” beyond cinematography, and it was not only generic but also historical and personal.

2

Impossible Project, 2008, Text, Dimension variable

Impossible Project, 2008, Text, Dimension variable

In 2008, the year I became personally acquainted with Koki Tanaka, the artist conceived a total of 50 actions for his Impossible Project. Each action was described in one English sentence, and each performance of these actions was equivalent to completing a piece of work by Koki. These actions were not so much absolutely “impossible” as very likely to be accomplished, but the artist accurately touched upon the frontier of our unawareness or unexpectedness, on which we may ask why these actions didn’t come into our mind, rather than regard them as impossible to do or achieve. The imagination about conception and creation was not the core of these instructional sentences. The “invitation” was the genuine significant part that gave this project critical agency. Each sentence resembled an invitation from a specific borderline, and each borderline emerged certainly from a discrete event or phenomenon. “All,” “every,” “any” and “to” were the keywords shared among these sentences. “All” and “any” primarily indicated the scope of action; “every” specified the thoroughness and particular moment of implementation; and “to” often implied transition or putting into practice. As a matter of fact, these instructions were the marks of borderlines to be crossed.

That is, in 2008, the year in which China began to strut its stuff to the world and the year when Stop-Rokkasho peaked (an anti-nuclear movement launched by Ryuichi Sakamoto against the opening of a nuclear reprocessing plant in the Japanese village of Rokkasho), Koki tried to employ the abovementioned four keywords to outline the real conundrums we confronted in the globalized world—we must put a question to all relational links; we must take whatever action is necessary!

Title: Walking Through

Year: 2009

Material: HD video

Time: 55 minutes

Following the discussion, it seems proper to revisit Koki’s earlier video works such as Everything is Everything and Walking Through, from which we can ruminate on the deeds and images attempting to intervene in everyday objects (mostly industrial products). These daily necessities and industrial products simultaneously point to two types of regulatory framework for our actions. One is the functional framework of our quotidian existence, and the other is the behavioral framework established by industrial objects. An extremely captivating visual effect as explosive as humorous finds expression in the transient performance, and the images obtained a two-fold implication from the dimension of dailiness. The structure behind and the humor in the dailiness lead to the fusion of objects’ normal textures and momentary delights in the world of images. The majority of Koki’s works created between 2003 and 2011 took the form of short video, in which objects manifested themselves as the “encounters” between individuals and the world. Each encounter, or meeting, brought an unexpected touch of humor, as if it was challenging our consciousness, making itself astonishing and meaningful. Precarious Tasks (2012) was Koki’s art project carried out after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Its spotlight shone not so much on “encountering the dailiness” as on “quotidian practice of encounter.” This project centered on “gathering” and the reflection upon the relational trinity of “society-culture-life.” The human-object relations were no longer represented by the encounter caused by any single action. Specific moments (moments of gathering), milieus (sites of gathering), and interactive communication (collective behavior) began to emerge, and the content of images changed drastically. Objects, or the human-object relations as the creative materials for this project, still lay in the core of images, while people who gathered together tended to move or work around objects with part of their bodies. Through the artist’s design, reading and recording, the focus of their actions was shifted from objects onto the contexts of their gathering, from which another borderline came into view: the precarious boundary between gathering and the world. It seemed that we can tackle (i.e. overstep) the precariousness of this boundary only by concrete gathering.

But what was to be crossed? It originally referred to Koki’s personal traversal of the dailiness characterized intuitively by the actions in his videos, so as to share it with the viewers, though in a relatively moderate degree. Nevertheless, Precarious Tasks unfolded in an multilayered fashion, be it in terms of the number of actions, the establishment of relations, the contexts of objects, the milieus of events, or the recording and editing of images. Perhaps we can draw a tentative conclusion from these results: it was a development unfolding from video to moving image. However, we should not treat video and moving image as two discrete media or forms simply on grounds of this preliminary conclusion. Koki’s art projects clearly illustrated the opposite, namely that the différenciation (or différentiation) between the two occurs at the moments when the relations between images and their immediate environments change, when the boundary between actions and the world is redrawn, and when individuals encounter globalized phenomena. In global events and disasters, therefore, the elusive geopolitics and pluralistic cultures firstly induced qualitative change in the relations between the artist and images, and the newly generated images in turn altered people’s relations to one another, thereby raising new questions and ideas. If video has enjoyed its legendary status due to its inquiry into the society (media), Koki seems to successfully reveal the strong possibility of the connections among real-life experiences, events and history, since he has traversed the everyday space-time and probed into the environment and the world on the one hand, and addressed human needs for relationships, the scales of aggregates of people, as well as the rheology of thoughts and images on the other as early as the dawn of the 21st century.

Koki Tanaka presented no spectacle of disaster, or, more specific, he refused to focus his works on disasters. In this way, how can he cope with disasters and the world? We may observe that, when confronting the realities of disasters, the artist utterly ignored the existing spectacles, and instead tried to uncover the underlying truth: the impossibilities manifested in our society and the continual occurrence of disasters in the real world have been faithfully mirrored in each individual and unfolded at precarious moments of all stripes in the interpersonal relationships. In short, realities do not dwell in sheer spectacles. The actualities of disasters originated not merely from physical realities and media representations, but also from the existence of each individual and each relational network. This was exactly the fresh revelation afforded by Koki’s Precarious Tasks and his ensuing art projects on collaboration and symbiosis. Facing up to “gathering” is a necessary commodity if we’re going to handle disasters. This is the direct yet measured response Koki formulated to the contemporary world. The phenomenon that “people no longer read and converse nowadays” was one of the driving factors behind his subsequent art projects, although this phenomenon has existed in our society long before the occurrence of disasters. The gatherings he devised and the responses he mounted almost echoed Bernard Stiegler’s explications of the fractures engendered by contemporary social problems, particularly the externalization of the memory function and the societal fractures caused by capitaldominated professionalization. As a result, Koki’s art projects alerted us to the fact that, nowadays, the perceivable urgency of tackling disasters is indeed closely linked with an age-old, far more fundamental issue, that is, the exploitation of energy resources at the expense of the eco-system is inextricably connected with the fragmentation of memories and the break-down of relationships. Yet, they are linked not so much by superficial causality as by over-determination and relational induction. In sum, Koki’s revealing insight, or, what his practice set great store by, was the observation that a slight change in the dailiness will affect everything else in our world.

Koki Tanaka, Precarious Tasks, Exhibition view at Mirrored Gardens, 2019

Koki Tanaka, Precarious Tasks, Exhibition view at Mirrored Gardens, 2019

3

According to my observation and rumination, all the elements in Koki Tanaka’s oeuvre, be it the moments of encountering objects, the gestures (action instructions) indicating the structural boundaries, the gatherings within specific contexts, the creation of collaborative experiences, the discussions on the scenes of encounter, and the follow-up visits to texts and sites, all involved the congruence between practices and purposes, after which the latter were incorporated into the conception and implementation of the former, and thenceforth retreated as questions. This process exhibited a reflexive quality, and gatherings, be it of objects or of people, serve as the fountainhead of such reflexivity. Besides, all the processes, happenings and outcomes (incl. individuals, groups of objects, and aggregates) of his art projects were aimed to search and experience the critical timing. In other words, art is powerful not so much because it is able to create social spectacles or solve social problems as because it can discern and grasp the sensitive, reflexive agency capable of penetrating phenomena and problems. This ability of art is important, given that human beings have been in a self-adjustment process vis-à-vis the existing frameworks and personal predicaments since the 20th century. It means that humanity has undergone a century-long period of “machine as method.”

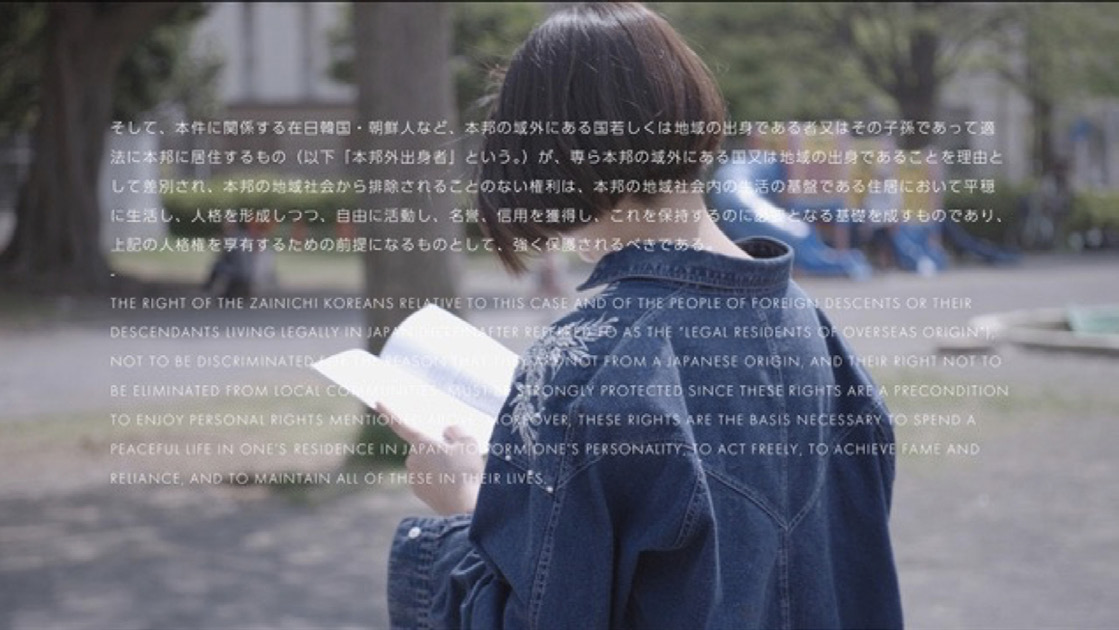

If individuals and phenomena in this world are linked by over-determination and relational induction, the gathering-generated reflexivity will not be directed back towards any single individual or subject, but instead shared among the participants and potential viewers as their N-dimensional reflexivity. It is evident in Koki’s manipulation of objects with a transient touch of humor. At the moments of action, metamorphosis or displacement, the objects in Koki’s gathering projects created a peculiar atmosphere (or a gaseous space) charged with prudence, anxiety and hesitation, urging the participants to do something “collectively” as a means of escape from this uncomfortable space. We may construe this process as a march or a momentum towards the environment. Humor ergo becomes delightful events incarnate that liberate our consciousness from the humdrum dailiness. Instead of treating the environment or nature as readily available, Koki was persevering in his attempt to penetrate or traverse the environment, so as to make it accessible and comprehensible to everyone. In his art projects, the environment was diversely comprehended by different individuals in a synchronic manner. What matters was not to grasp the individuals’ intrinsic identities, but to weave their different understandings into a correlative space-time. As far as Koki was concerned, the gatherings of reading, collaboration and symbiosis were aimed not so much to fulfill any utopian ideas as to place oneself in the environment created by traversal via the gatherings. As the “histories of the vulnerable” came under the spotlight of Koki’s art project, he first of all constructed an internal narrative space with correspondences. Photos and discourses were then installed into this space by the image of the two protagonists’ encounter. The recordings of the classes were presented as multiple dialectical relationships among different archives, including (1) the math course specifically offered to Korean expatriates in post-war Japan; (2) the arguments over identity and law; (3) the protagonists’ reading of related clauses and follow-up visits to the sites of events that turned the action of reading into the catalyst for

Video stills, Koki Tanaka , Of Walking in Unknown , 2017, Video

revealing the historical and social structures embedded both in the texts and sites; (4) the thriller- and road movie-like dialogue in car; and (5) the gathering of the artist, the protagonists and the other participants in a coffeehouse where the artist prepared cocktails and dishes for the protagonists. Here, “environment” was no longer represented by images, but a reality forged through the image producer’s labor, a concatenation of procedures for confirming and manipulating the critical timing. In the succession of Koki’s art projects as serene as brilliant, “the environment always showed an endless stream of energy.” To admire Koki’s oeuvre is to take a voyage of discovery through a land of great strength and intensity, from which I learned that art is highly competent to resist the simulacra of nature and the society of automation.

Text ©Author, 2019

Photo©Photographer, Koki Tanaka, 2019

Courtesy of Artist and Vitamin Creative Space

[ About the Artist ] >>

“Koki Tanaka:Precarious Tasks”, exhibition views at Mirrored Gardens, Guangzhou, 2019.

Courtesy of the Artist and Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2019.

All works of art by Koki Tanaka ©the Artist, 2019

____

Koki Tanaka: Precarious Tasks

24 Jan. – 31 Mar. 2019

Mirrored Gardens, Guangzhou