Light Within (Part 1)

The universe contains a righteousness

that flows through all things,

from the rivers and mountains below

to the sun and the stars above.

– Wen Tianxiang, “Song of Righteousness”

Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing wonder and awe, the oftener and the more steadily I reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.

—— Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

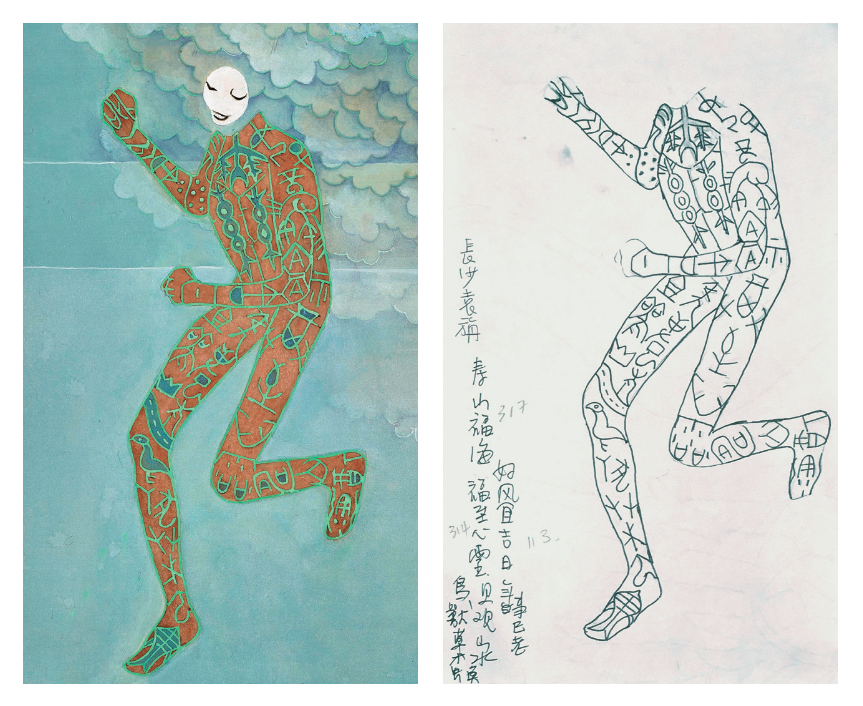

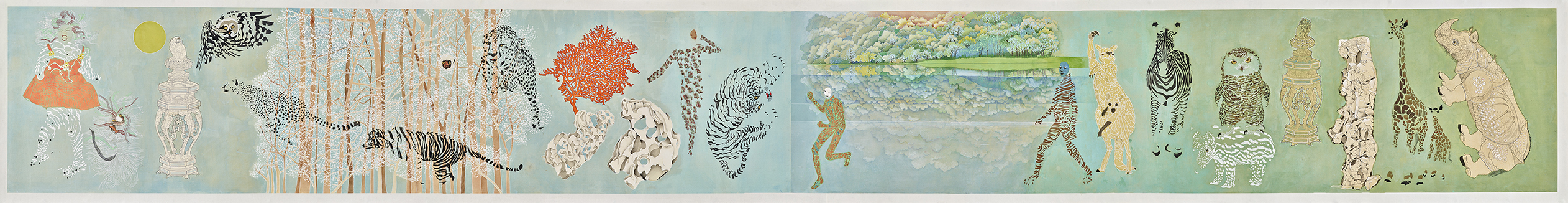

* Upon opening the long horizontal scroll of Hazard Path, we seem to see a dramatic re-enactment of the cycle of life. The complexity of the artwork is packaged within a plainness reminiscent of Chinese opera sets: much space left empty, the background a primordial vacuum. The performance begins with a rhinoceros, that ancient and vigorous animal, successively followed by a mother giraffe, a Taihu stone standing on its side, a lamppost carved from stone (an image lifted from Li Gonglin’s Drawing of Vimalakirti Lecturing), an owl, a zebra, a mother kangaroo, and a striped person with a blue face. They lead our gaze toward a stretch of the journey with exquisite scenery: a colorful forest, reflected in the surface of a lake. On its other side, an apparently fleeing person, her entire body covered with oracle-bone inscriptions, including the words “Changsha Yuan Jai”: the hometown that the artist cannot banish from her memory.

(Left) Yuan Jai, Hazard Path (detail), 2016, ink and color on silk, 47 × 396 cm.

(Right) Yuan Jai, sketch for Hazard Path, an apparently fleeing person, her entire body covered with oracle-bone inscriptions, including the words “Changsha Yuan Jai”: the hometown that the artist cannot banish from her memory.

We sweep past a tiger’s stripes, a fleeting human shadow concealed amid mountain peaks, and blood-red coral that evokes a Zen koan: “every branch of coral holds up the moon.” Then we enter a different forest, a white ape perched in its branches, fleet-footed pumas charging amid the trees, and an owl startled into flight toward the bright moon.

When the stone-carved lamppost appears again, the rays of light around it have changed as if with the passing of seasons, marking the ephemerality of time, and we finally encounter the young girl with a brightly colored dress and the body of a leopard. She faces us, dancing wildly, her hair hanging loose, her mouth open as if to shout or sing. Yuan Jai claims that when her granddaughter saw this part, she exclaimed: “grandma’s crazy!”

Yuan Jai, Hazard Path(detail), 2016, ink and color on silk, 47 × 396 cm.

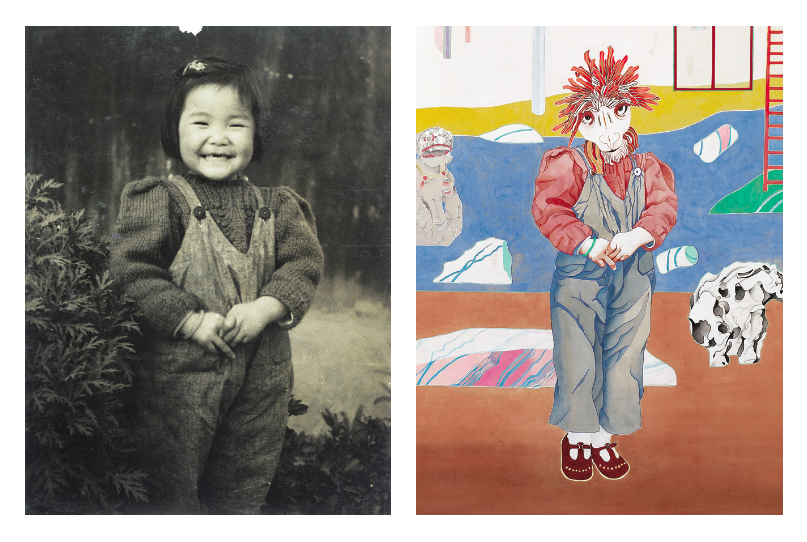

* Yuan Jai painted Hazard Path in 2016, at the age of seventy-five. Five years before, she had painted Reaching Seventy, a painting that includes an image of herself at the age of five drawn from a photograph. At the time of the photograph, World War II had just ended, and Yuan Jai was still in Chongqing. The photograph shows an innocent girl with no inkling of the great vicissitudes that awaited in China’s destiny.

(Left) Yuan Jai at the age of 5 in Chongqing.

(Right) Yuan Jai, Reaching Seventy (detail), 2011, ink and color on silk, 190 × 90 cm.

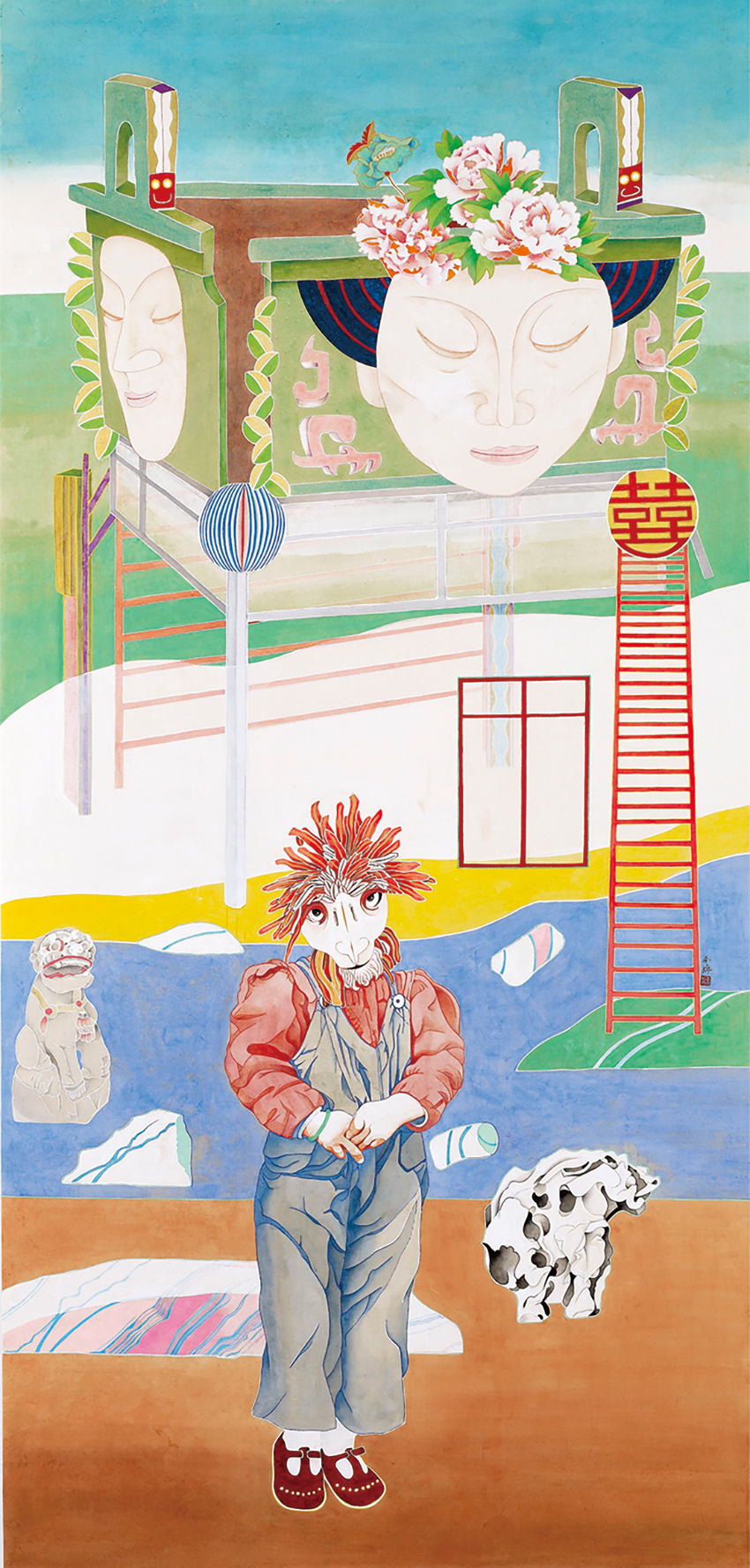

In the painting, the child’s face is transformed into that of an eagle. The girl’s left hand holds her right thumb, forefinger and middle finger—the fingers used to hold a paintbrush—in a portent of her future as an artist. The Taihu stone, stone lion, and stream behind her suggest a garden-like space. A ladder leads upward to an image of the Da He Ding, a massive bronze vessel that was used for important rituals during the Shang Dynasty. However, the male face on the side of the vessel has been transformed into a female visage, her eyes serenely averted, as if she calmly awaits everything that will occur. And the “Double Happiness” character at the top of the ladder seems to corroborate the child’s unwavering connection to art and culture.

Yuan Jai, Reaching Seventy, 2011, ink and color on silk, 190 × 90 cm.

* In order to appreciate these portrayals of the journey of life, we should first allow ourselves to experience an imagined transformation, just as the artist converts the invisible process of spiritual growth into figurative forms that combine human and non-human forces. These forms illustrate what might be called a poetic root-seeking; a journey backward in time; a forging of spiritual sublimity; or a “transcendent response”[1] that traverses space and time. This manner of mental craft, all but lost in contemporary times, allows a reawakening of sensitivity to the connection between all living things. The artworks also offer us a moment of experience that relates to both the past and the present, that recalls T.S. Eliot’s description of “historical sense” that “involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence … this historical sense … is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and of the temporal together.”[2] Thus the historical artefacts and implements that appear in Yuan Jai’s paintings are neither props nor allusions; rather, they are vessels of common cultural memory, waiting for us to encounter them, when they reanimate as vital forces of association.

* If we trace back what Walter Benjamin said, “the art of storytelling is reaching its end because the epic side of truth, wisdom, is dying out,[3] then Yuan Jai revives the narrative potential of Chinese painting by continuously positioning the narrative within the relationship between the individual and history. She explores the cultural ecosystem cultivated by individual life experience, thereby developing a series of cultural narratives. Only by locating these narratives within continuous—rather than fragmented—cultural processes can the artist enter into the realm of life philosophy through the composition of a painting. I compare this accomplishment to the creation of a hidden garden: in order to return to this garden, its creator must first leave it, and perhaps even become a stranger to it.

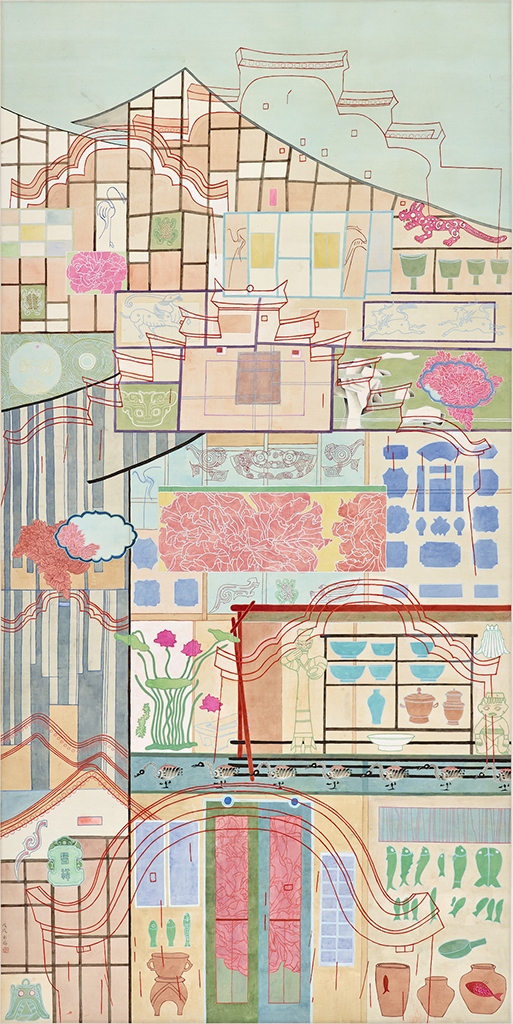

Yuan Jai, Nature Within (A Room Possessing Delights of Forests and Streams, Humans Sharing the Spring with Heaven and Earth), 2016, ink and color on silk, a set of two, 203 × 89 cm / each.

* From the series Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (2007) to Amor Fati (Love of Fate) (2017), from Garden in the Mirror (2014) to Nature Within (2016), Yuan Jai’s paintings consistently suggest the existence of a garden space, which we can interpret as a response to the modern, exorcised world, violently changing and always accelerating. The paintings extend this sheltering and transformative space to yet broader fields, whether it is the intimacy with the “small beasts” depicted in We Can be Friends (2008) or the homage to the nurturing mother, situated between human and animal, depicted in Mother Earth (2014). In this way, Yuan Jai’s paintings contain explorations of the primeval world in which humans and all other species deserve to live.

“The earth is full of refugees, human and not, without refuge.” This is how Donna Haraway describes the predicament of contemporary humanity and the planet. “We are facing the production of systemic homelessness. The way that flowers aren’t blooming at the right time, and so insects can’t feed their babies and can’t travel because the timing is all screwed up, is a kind of forced homelessness. It’s a kind of forced migration, in time and space.”[4] The artistic world of Yuan Jai helps us realize that a refuge and homeland possibly exist. Her art inherits the “Shanshui” spirit in the traditional sense, but is no longer limited to depicting a certain concept of natural order within cultural conventions.

Yuan Jai, A Faraway Place, 2018, ink and color on silk, 207.3 × 103.2 cm.

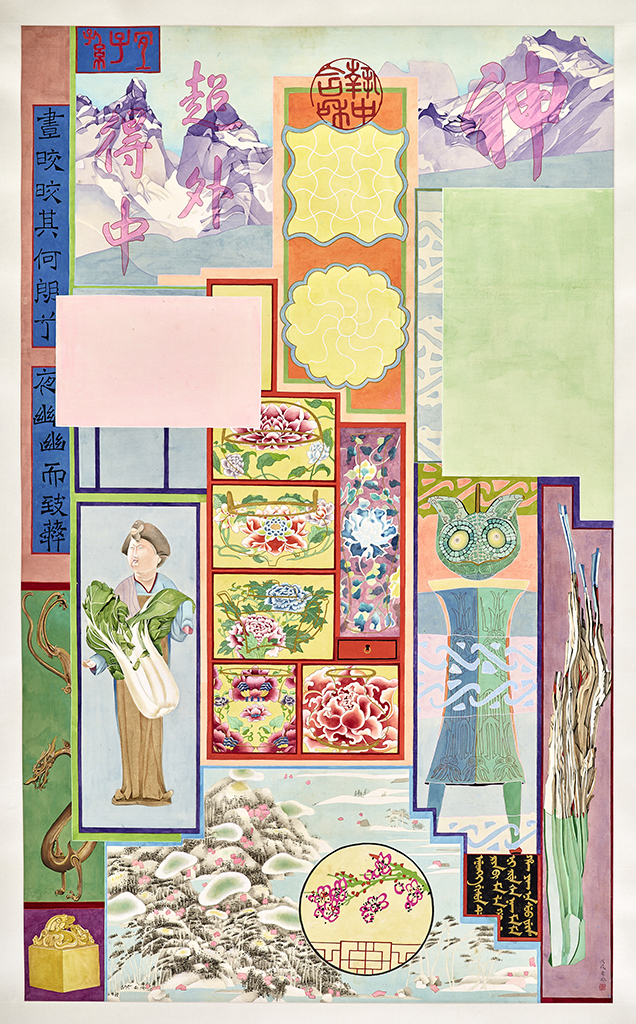

Yuan Jai, Pavilion of Treasures, 2018, ink and color on silk, 178.1 × 107. 8 cm.

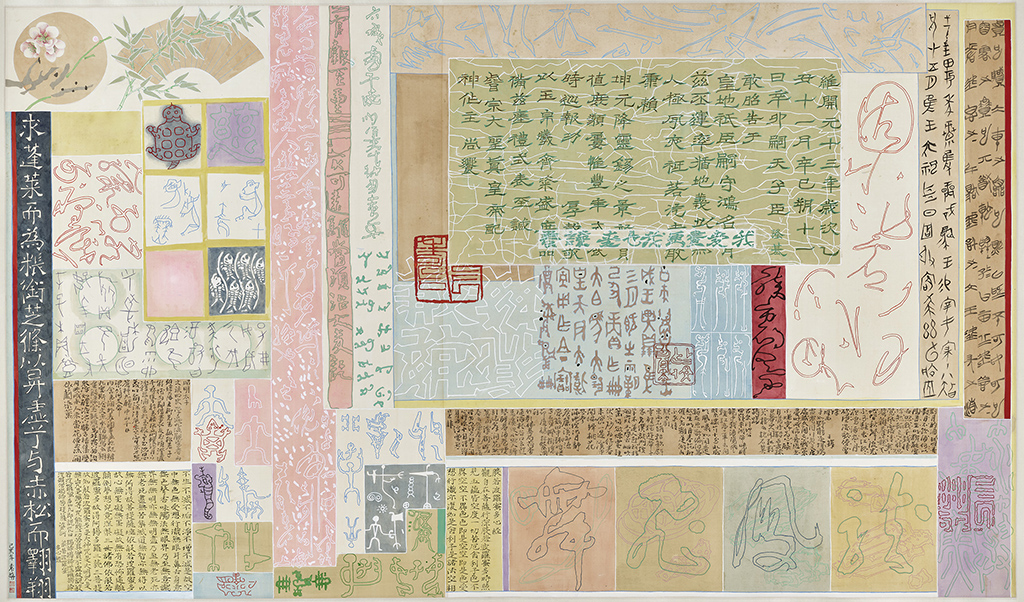

* Created in 2018, Pavilion of Treasures and A Faraway Place draw on two disparate principles of space within Chinese culture: the former, imperial, the latter, common. Yuan Jai’s brush produces the imagery of a museum of communal culture. She interprets her memories of an ancestral temple from her father’s photographs in Cultural Hall of Calligraphy (2008); then, eleven years later, she further develops this idea in I Love to Paint and to Read as Well (2019). These paintings exemplify Yuan Jai’s extensive considerations of the endless potential of spatial montage in ink painting, as well as her adept exploration of Shu Hua Tong Yuan (the common origins of painting and calligraphy)[5].

Yuan Jai, Cultural Hall of Calligraphy, 2008, ink and color on silk, 130 × 213 cm.

Yuan Jai, I Love to Paint and to Read as Well, 2019, ink and color on silk, 104 × 177.5 cm

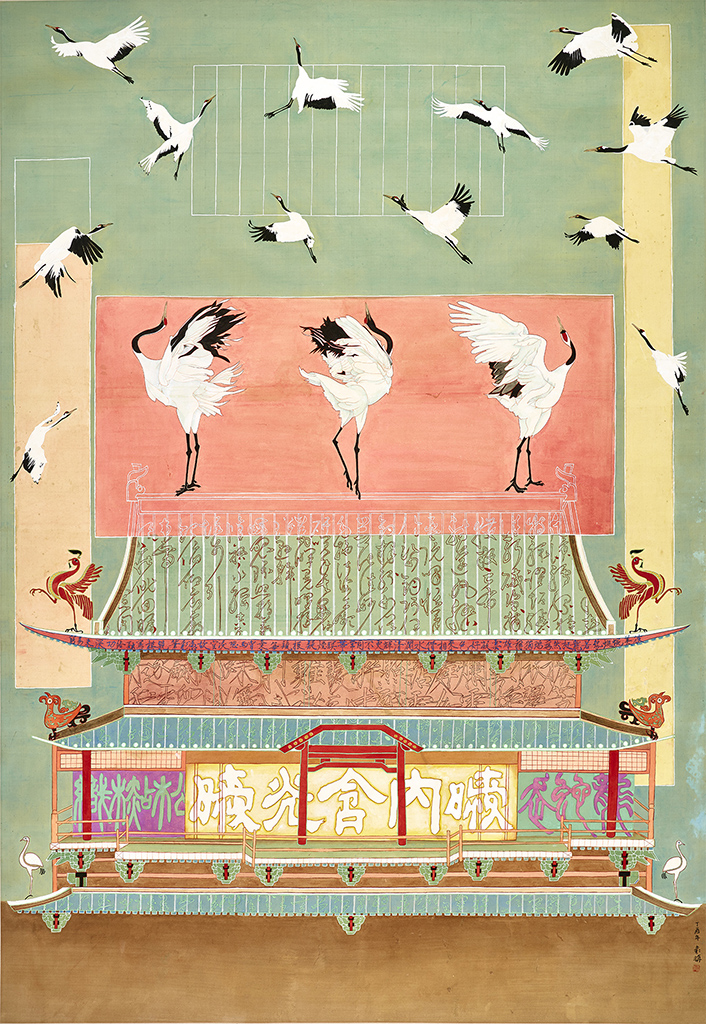

* The place that Yuan Jai invites us to enter is a world in which the value of life is reverently protected, and cultural dynamism is continuously pursued. In Auspicious Cranes (2017), the words appear on the building are an epigraph from the late Han poet Cui Yuan: “The Light Contained within Darkness,” hinting at Yuan’s interest in the light of morality and virtue. This calls to mind Magnificence(2017), in which the artist attempts to capture the radiance of flame, though its form and void both remain invisible. Yuan Jai adopts an egoless approach to lending form and color to that which is intangible, and allowing vitality to flow therein.

Yuan Jai, Auspicious Cranes, 2017, ink and color on silk, 171 × 118 cm.

(To be continued, read more on “Part 2”)

Text: Hu Fang

Courtesy of the Artist and Vitamin Creative Space.

All art works by Yuan Jai © the Artist

[1] In The Question Concerning Technology in China : An Essay in Cosmotechnics, Yuk Hui observes: in Chinese cosmology, we find senses other than vision, hearing, and touch. They are referred to as 感应 (gǎnyìng: perception), characters that imply 感觉 (gǎnjué: feeling) and 响应 (xiǎngyìng: response). These perceptions are generally understood as “correlative thinking” … this is not merely the product of subjective contemplation, but rather, something that emerges from the resonance between humans and the heavens, which are the foundation of morality.

[2] T.S. Eliot, “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” Eliot: Collected Works, Wang Enzhong ed., International Culture Press, Beijing (1989), p. 2. Chinese.

[3] Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller,” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, Hannah Arendt ed., Zhang Xudong, Wang Wen trans., Sanlian Press, Beijing (2014), p. 98. Chinese

[4] Donna Haraway, “Post-Truth, Climate Crisis, and New Political Imagination,” The Paper: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_3753029

[5] In the book of Art as History: Calligraphy and Painting as One, Wen C. Fong gives an intensive survey through the close historical relationship between calligraphy and painting and their primacy among Chinese arts, he brings new and revised views on a broad range of the important subject of “Shu Hua Tong Yuan.”