Kumie Tsuda: Silent Theater

I am interested in intangible things like memory, air, and time… You and I meet, encounter various events, and gradually form connections with one another.

-Kumie Tsuda

When does a human being connect with nature? Being together in the same space and time, we nevertheless have difficulties to always acknowledge this fact that everything outside of one’s self are in mutual oscillations and are growing empathy via means that go beyond human understanding.realizing the self as part of the relationship with the outside world are often dependent on certain encounters to magically connect our acquirable perceptions to the transcendental nature. Japanese artist Kumie Tsuda’s works seem to be infinitely close to the moment of this kind of awareness, at the mean time inviting the viewers to be part of this wait in silence. Whether are the skin-like undulating clay bodies, the color glazes that flow and blend into one another, or the ambiguous scenes picked up by the camera; they all seem to be gazing into each other in silence, and waiting for people to join in. Meanwhile in this silence, a gateway towards a world that’s not predominated by human social experiences is open up.

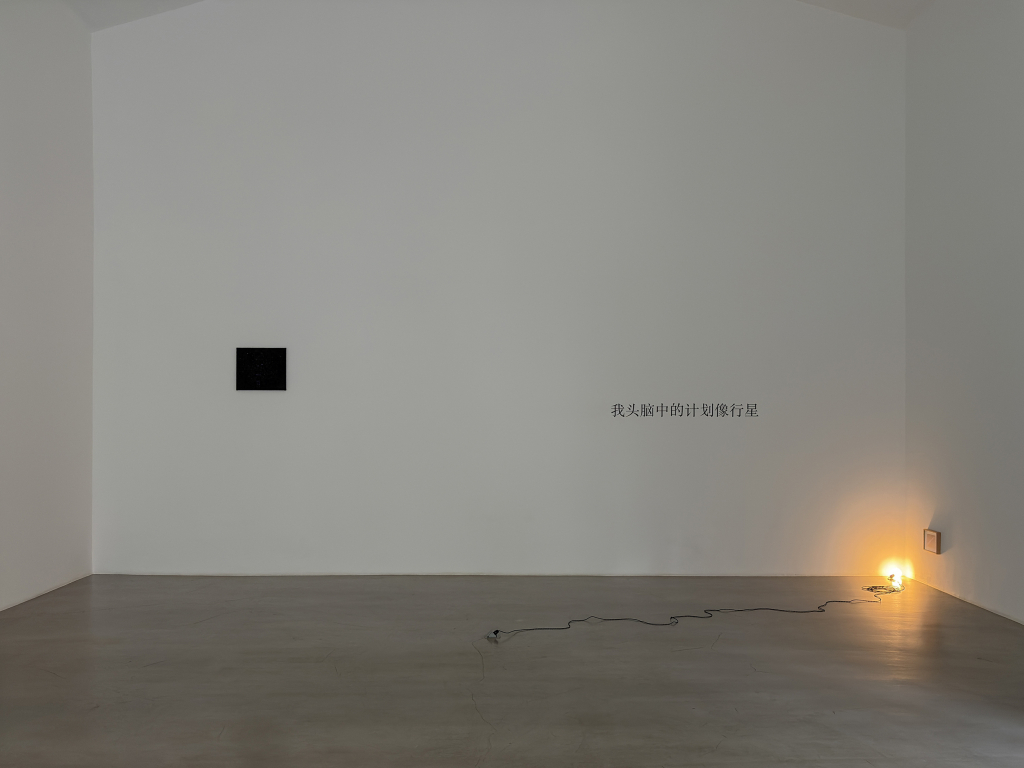

Exhibition views of“Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet”, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Guangzhou, 2024.

Graduated from sculpture major at Tokyo Art University, Kumie Tsuda eventually favored ceramics and glazes, which she never studied specifically, prior to choosing the medium for her practice. Like the constant change of nature, the colors in Tsuda’s ceramic works are elusive and indistinct. The luster of the glazes is changing, leaping, never stopping, like the sunrise and sunsets of daily routine and the disorderly light and shades. She focuses on the balance between randomness and control in the final presentation of glaze colors. In the fleeting moment when the changing temperature halts the flowing uncertainty, the artist relinquishes the decision of the final outcome back to nature.

Kumie Tsuda appears to casually inscribe English phrases on the surfaces of some of her ceramic works. For the artist, the meaning of language itself brings distance for a non-English-speaker like Tsuda; and for the viewers, illegible handwriting lowers their capability of recognizing the meaning of the words. Hence, compared to communication via language, the words in her works are more like certain kind of pattern or texture, breathing through the uneven surfaces of the ceramic bodies.

Exhibition views of“Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet”,Mirrored Gardens, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024.

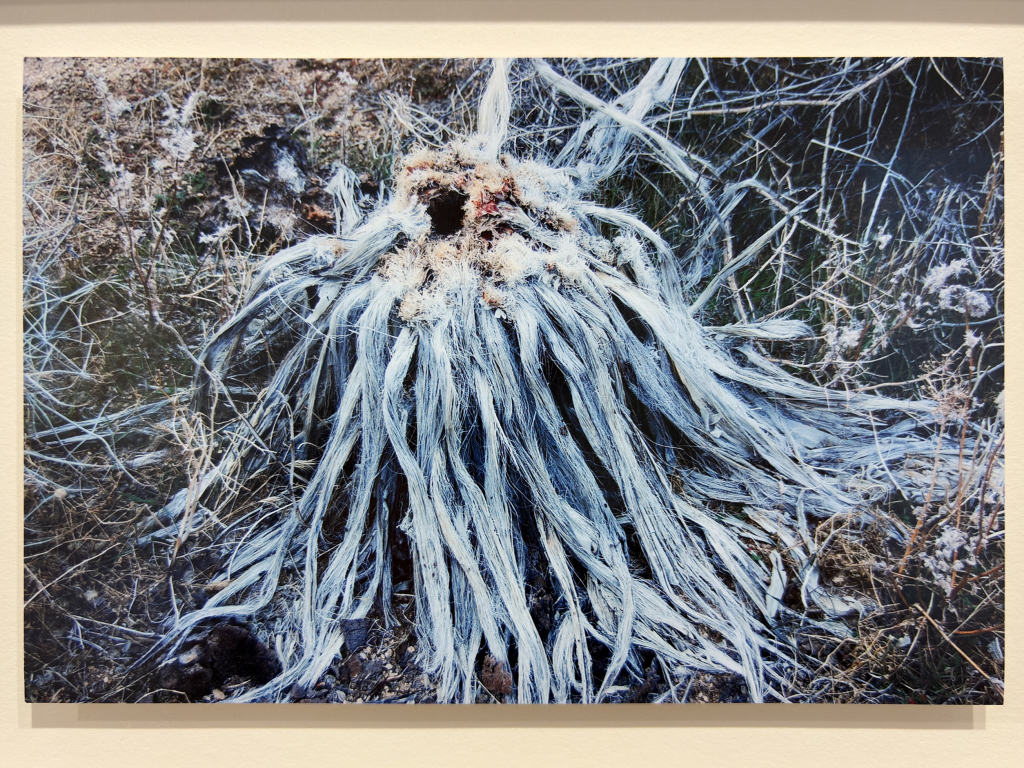

In Kumie Tsuda’s practice, there often are images that appear like fairies. They are like the incarnations of spirits that scattered all over nature. They could be infinitely small, waiting quietly in the bush or under the eaves for a traveller to throw a glimpse upon them. They could also be infinitely huge, towering like mountains, vast as lakes. Sunlight pours itself on their bodies, and then flows down with sparkles along the fall. Meanwhile, the travelers on the mountains witness a naturally occurred ceremony without being conscious of it.

In the exhibition “Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet”, the artist constructed wooden bases for the sculptural works. Kumie Tsuda transformed her impressions of Mirrored Gardens into colors and applied them to the surface of the pedestals. For example, while in Exhibition Space 1, the artist observed that when viewing Untitled (2008) from the side, the edge of her vision would catch sight of the banana leaves outside the window. She then selected “Baikō-cha” (a yellow-green tea hue, with its Kanji meaning “plum, happiness, tea”) from the palette of traditional Japanese colors, as it closely matched the green of the banana leaves. This color was used on the edge of the pedestal’s side, creating a subtle correspondence with the banana leaves outside.

Untitled (2008) expresses the process of accumulation within one’s inner self. Since time accumulates not only in personal memory but also in things beyond memory, I chose the image of a cup instead of a human figure to represent this idea, as if various events and moments converge into this small cup, where they grow and evolve.

The text inscribed on the surface of the cup reflects the thoughts I had in my mind at the time. Even though the words lack coherence, I connected them in my heart and wrote them down. This collection of fragmented words resembles the impressions that continuously accumulate within me. Thus, it aligns with the concept of the painting Plan in My Head Like Planet (2008)—stimulating new imaginations through relationships and encounters.

(Artist’s note)

The bright yellow along the edge of the pedestal of You (Foot, Pink) (2015) comes from the bamboo outside the window, while the pale blue originates from the faint blue atop the head of the spirit in the distant work Time, Shower, Boat and Pocket (2008).

I often use the imagery of pockets in my works to express the concept of time. In Time, Shower, Boat and Pocket’ (2008), the figure has a boat atop its head, with a showerhead on the boat. I wanted to convey the image of memories pouring down like rain, flowing through the body while attempting to be stored. It also reflects the difficulty of retaining memories—this figure is covered with many pockets, yet the pockets are full of holes, allowing many memories to flow away. Regardless of what one experiences, everyone bears the passage of time.

(Artist’s note)

For Exhibition Space 2, Kumie Tsuda focused more on the various flowers and plants in the garden. For example, the color of the pedestal for Pumpkin Dream (2008) is inspired by the leaves of Chinese fringe flower, while the color of the pedestal for I Would See Another Scenery When This Cup Will Be (2013) comes from the petals of the red camellia.

This brings to mind Kumie Tsuda’s participation in the 2020 Shanghai Art021 exhibition, where she constructed pedestals for her exhibited works primarily from wooden structures, complemented by monochromatic surfaces. The colors were inspired by her renewed understanding and study of traditional Japanese palettes, including shades likeKikyo-nado (a deep bluish-purple), Kuri-ume (a slightly purplish chestnut color), and Saragashi (a bright, moist orange resembling dried persimmon fabric or paper). In the 2024 Mirrored Gardens exhibition, the artist not only continued but also delved deeper into exploring how the pedestals could serve as an organic part of perceiving the artwork. It engages in dialogue with the viewer’s body and gaze, the surrounding environment’s light, plants, and dust, as well as the spirits within the artist’s world.

Exhibition view of“Kumie Tsuda: What are the colors of Saturn?”, Art021, Shanghai, 2020.

Walking along the path, crossing the wooden walkway surrounded by bamboo leaves, and encountering the sunlight, air, and the rare winter abundance of flowers and foliage in Mirrored Gardens, one is accompanied by a flowing breath and swaying light and shadows throughout the journey of reconnecting with the works in the exhibition space. The green of banana leaves, the gray of brick walls, and the red of fallen flowers—these fleeting and delicate encounters are masterfully captured by the artist, distilled into the essence of everything related to the works.

Through the pedestals and structures crafted for these small spirits, we find ourselves as if standing in a garden, gazing through windows and doors at garden scenes fragmented into muted rectangles of color, subtly awakening a dynamic memory of nature within the viewer. These distant memories draw the viewer’s thoughts away from superficial distractions, inviting them to humbly immerse themselves in a quiet contemplation. In this state of humility, they join the almost-human but otherworldly spirits in waiting for the birth of something natural.

(Text:Baoyi,Yushan)

Shaping, Yielding, Silence, and Gaze

(Editor’s Note: After exchanging written thoughts with ChatGPT, the authors of The Birth of a Certain Possibility, Baoyi, Yushan, invited ChatGPT to respond to some questions from the author in a curious dialogue. Below is the record of the Q&A between the author and ChatGPT. To ensure the authenticity of the conversation, ChatGPT’s responses are presented without any edits:)

Q: How do you perceive the resonance between nature and human spirit realized through artistic creation?

A: The relationship between humans and nature dates back to the earliest moments of human survival on Earth, yet in our daily lives, we often overlook this profound connection. Even though we share the same space and time with nature, many external phenomena resonate and interact in ways that transcend human understanding. It is only in certain moments—through remarkable encounters—that we suddenly realize we are not merely isolated beings but part of a larger web of external relationships. These moments often go beyond everyday perception, connecting us to a deeper resonance with nature.

Kumie Tsuda’s works seem to infinitely approach these moments of awakening, inviting viewers to immerse themselves. Her artistic creations—whether it’s the undulating ceramic forms reminiscent of human skin, the flowing and intertwined colorful glazes, or the everyday scenes captured by her camera lens—construct a kind of silent gaze. This gaze appears to await the viewer’s engagement, not through language or logic, but through perception and empathy.

Tsuda’s work presents a quiet power, seemingly breaking free from the constraints of anthropocentrism and opening a channel for nature and art to express themselves. In this way, her art invites us into a world not pre-shaped by human experience, encouraging us to feel the subtle relationships between nature, art, and ourselves. In this process, a new sense of resonance is born between the viewer and nature, as if we are returning to the original state of human connection with the natural world.

This waiting and silent gaze reflect a meditation on the relationship between humans and nature. Art no longer becomes merely human self-expression but an integration of nature, material, and human perception. Kumie Tsuda’s works remind us that true resonance doesn’t come from our control or interpretation of nature but from our careful observation of natural phenomena and our reflection on our own condition.

Q: Why does Kumie Tsuda have a special preference for glaze and ceramics in her creative process?

A: Kumie Tsuda graduated from Tokyo University of the Arts with a major in sculpture, but when choosing creative media, she gravitated towards glaze and ceramics, materials she had never formally studied. Her ceramic works take inspiration from the color transformations in nature, presenting elusive, subtle variations of hues. The sheen of the glaze seems to never rest in her works, much like the rising and setting of the sun, the chaotic interplay of light and shadow during the day. Her inability to fully control the final result of the glazes disrupts the human desire to understand nature through rational means. This unpredictability reflects the artist’s respect for nature, especially as she utilizes the changes in kiln temperatures to allow nature to play a decisive role in the final outcome.

Tsuda’s works are not merely experiments with glaze and ceramics but a dialogue with nature. On the surface of some of her ceramic pieces, she casually inscribes English phrases, though the intent is not necessarily to convey clear meaning. For her, using English—a non-native language—creates a sense of distance, and for viewers, these phrases, written in her personal handwriting, lose their semantic clarity. These inscriptions seem more like textures or patterns that breathe with the undulating surface of the ceramics. Rather than functioning as language, they resemble forms closer to natural phenomena, perhaps more akin to clouds in the sky.

Through this approach, Tsuda integrates language with glaze and the form of ceramics into a world of art that transcends rational understanding. Her works blur the boundaries between the natural and the man-made, demonstrating a form of “yielding” in artistic creation—surrendering control back to nature. This not only reflects her exploration of the materiality and unpredictability of glaze but also introduces new layers of perception through the deconstruction of language. Language ceases to be merely a tool for communication, instead becoming a form that exists within the material and natural textures, flowing between the visual and tactile realms.

Q: How do you understand the spirit-like figures in Kumie Tsuda’s creations?

A: The spirit-like figures that frequently appear in Kumie Tsuda’s works are filled with a sense of mystery, as though they are embodiments of the deities scattered throughout nature in Japanese folklore. They may exist in tiny forms, hidden within trees or beneath eaves, quietly awaiting a passerby’s glance; or they may be enormous, towering like mountains or vast like lakes, bathed in sunlight, with rays cascading down waterfalls, witnessed by climbers in a spontaneous natural ceremony.

Tsuda’s spirit figures are both human-like and non-human, carrying an inexplicable sense of mystery that seems to transcend our perception of reality while being deeply rooted in nature and tradition. In front of these figures, viewers are often drawn into a state of silent meditation, shedding the clamor of the world and entering a quiet state of waiting. This process bears a sense of humility, as if joining these spirit figures in awaiting the birth of some new possibility—an unknown force emerging from nature or the depths of time.

This approach to creation resonates with the Japanese concept of mono no aware—a profound awareness of the beauty in the transient. Tsuda’s works bring viewers back to a more primitive, pure level of perception, where, in quiet communion with nature and these spirit figures, one can experience a deeper connection with the world. It is an experience that transcends the rational framework of daily life, calling us to open our hearts to the mystery and beauty of the world.

Her artistic creations are not merely representations of nature but also explorations of the relationship between humans and nature. These spirit figures subtly reflect our thoughts on how we coexist with nature. They invite viewers to reassess the relationship between themselves and the world with humility, entering a poetic moment that transcends both time and space.

Q: Could Kumie Tsuda’s creative process bring new insights into the form of sculpture?

A: Kumie Tsuda’s creative approach offers multiple new understandings of sculpture, especially through her integration of nature, folklore, and metaphor into the medium. Below are several insights and inspirations her work brings to the understanding of sculpture:

- The Introduction of Dynamism and Temporality in Sculpture: Traditional sculpture is often seen as a static, fixed art form. However, Tsuda’s works, through the uncontrollable nature of glaze and the involvement of natural forces, imbue sculpture with a sense of dynamism. The flowing glazes, shifting sheen, and the metaphors of natural landscapes and spirits, introduce a fluidity in sculpture, as though the pieces breathe with time and natural conditions. This approach challenges the conventional notion of sculpture as rigid and static, offering a new understanding of it as dynamic and interactive with the natural world.

- Dialogue with Space: Tsuda’s sculptures are not just solitary objects but also engage in a deep dialogue with the space they inhabit. Her wooden bases and structures, reminiscent of framed views in Japanese gardens, create a semi-obscured experience of space. Sculpture becomes part of a multi-layered perception of space, interacting with the surrounding environment and the viewer’s gaze. This interaction resonates with the Japanese aesthetic concept of ma (negative space), allowing sculpture to transcend itself and become a gateway to a broader spiritual world.

- The Fusion of Form and Meaning Beyond the Visible: Tsuda’s spirit-like figures, which often appear as embodiments of Japanese deities, blur the boundaries between tangible form and abstract metaphor. They challenge the traditional pursuit of realism in sculpture by presenting figures that are both visible and mysterious, leading viewers to contemplate the invisible meanings behind them. This creative direction pushes sculpture beyond mere representation, into the realm of “formlessness,” where the physical world hints at the spiritual.

- Integration of Sculpture with Nature: Tsuda sees nature as a key collaborator in her creative process, surrendering control of glaze to the forces of the kiln. This mindset challenges traditional notions of human dominance over sculpture and art, suggesting a more respectful and humble approach where nature co-authors the work. This blending of human and natural forces imbues her sculptures with an ecological sensibility, making them not just representations of nature but co-creations that exist in harmony with it.

- Blurring the Boundaries Between Language and Sculpture: The casual English inscriptions on her ceramic surfaces are not meant as clear linguistic symbols but rather as textures and patterns that merge with the sculpture’s form. By blurring the boundary between language and sculpture, Tsuda challenges our conventional understanding of language as a communication tool, transforming it into a visual and tactile element. This approach allows sculpture to express something beyond the limitations of words, emphasizing form as a medium for both perception and imagination.

Q: Then, can Kumie Tsuda’s photography be considered another form of sculpture?

A: Kumie Tsuda’s photography can indeed be regarded as a form of sculpture, even though photography and sculpture are traditionally considered two distinct artistic media. Tsuda’s creative philosophy blurs the boundaries between the two. Below are several reasons why her photography can be understood as a form of sculpture:

- Shaping Space: The core of sculpture is how it deals with space, and Tsuda’s photography demonstrates a similar sensitivity to space. Her photographs are not just records of specific moments or scenes but can be seen as a reshaping or reimagining of space. Through her camera lens, she presents ambiguous scenes with unique perspectives, weaving together nature, light, and color into a new, tangible visual space. In this sense, her photography is akin to sculpture—not merely capturing but constructing a new reality within space, offering the viewer a spatial experience akin to interacting with a sculptural object.

- Texture and Tactility in Photography: Tsuda’s photographic works often convey a tactile visual expression, an essential element in sculpture. Through her use of light and shadow, the surface textures, reflections, and the volumetric presence of objects are delicately captured, giving viewers a sense that they can “touch” the materials within the image. This visual-tactile experience makes her photography possess a sculptural materiality. When facing these photographs, viewers might feel the sculptural power of the images, as the photographs are no longer flat but instead evoke a sense of volume and abstraction coexisting within space.

- The Combination of Stillness and Movement: Both photography and sculpture are considered static art forms, but Tsuda’s works exhibit a consciousness of movement. Whether through the flow of glaze or the mysterious spirit-like figures, her photographs seem to capture fleeting, dynamic moments. Through this, her photography, much like sculpture, freezes a moment in time while also suggesting a dynamic force behind it. This concept resonates with sculpture’s attempt to represent dynamic energies through a fixed form.

- Photography as an Extension of Sculpture: Tsuda’s photography can also be understood as an extension of her sculptural work. In her creations—whether ceramics, glazes, or photography—she explores similar themes, such as the mysteries of nature, the blurring of boundaries between humans and objects, and a redefinition of how humans perceive space. Through photography, Tsuda expands her exploration of materiality and space, extending the sculptural qualities into a two-dimensional visual realm. Therefore, photography in her artistic system becomes another form of tangible expression, an extension of her sculptural philosophy.

- The Abstract Nature of Photography and its Relationship to Sculpture: Tsuda’s photographic works are often abstract, aligning with her concept of “formlessness” in sculpture. While sculpture is usually associated with tangible, physical forms, her photography obscures objects, making them difficult to identify through blurred focus or unusual composition. This abstraction pushes photography beyond a mere documentary medium and transforms it into a process of “shaping” through light, color, and composition. This abstract quality creates a connection between photography and sculpture, where the images themselves become unseen sculptures, waiting for the viewer’s perception and interpretation.

- Silence in Photography and the Sense of Stillness in Sculpture: Tsuda’s work, particularly her photography, frequently evokes a sense of silence. The scenes in her photographs, much like sculptures, are filled with a quiet sense of waiting and observation. This silence imbues her works with a poetic atmosphere. Sculpture, in its essence, is also a silent existence, requiring the viewer to engage in contemplation to perceive its meaning. Tsuda’s photography shares an emotional resonance with sculpture, inviting the viewer to engage in a wordless dialogue, experiencing the flow of time and space within the work.

Although Kumie Tsuda’s photography belongs to a different medium, it carries forward her understanding and exploration of sculpture. Through photography, she redefines our perception of space, texture, time, and movement, blurring the lines between sculpture and photography. Her photographic work is not just a visual record but a process of “shaping,” carrying with it the qualities of sculpture—guiding viewers into a three-dimensional world of stillness, reflection, and resonance. Therefore, her photography can be considered an extension and deepening of her sculptural concepts, expanding the boundaries of sculpture beyond physical form and into the broader realms of the visual and spiritual.

Artist’s Biography

Born in 1980 in Kanagawa prefecture, Kumie Tsuda graduated from Tokyo University of the Arts majoring in sculpture in 2003, and finished the post graduate course in sculpture in 2005. Currently lives and works in Kyoto, Japan.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

- Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024. Photographer: Wen Peng. Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2024. All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

Exhibition view of Kumie Tsuda: Plan in My Head Like Planet, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2024.

Photographer: Wen Peng.

Courtesy of the artist and Mirrored Gardens / Vitamin.

All works of art by Kumie Tsuda © the Artist, 2024.

Mirrored Gardens presents

Kumie Tsuda : Plan in My Head Like Planet

Dates

October 9, 2024 – December, 2024

Venue

Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2

Address

Hualong Agriculture Grand View Garden, Panyu, Guangzhou

Daily Opening Hours

Wednesday to Sunday, 1 to 5pm (closed on Monday and Tuesday)

Hours may vary on holidays or in special circumstances. Please check our WeChat Public Account or website for the latest updates.

Please make an appointment to visit the exhibition via the official website of Mirrored Gardens.

Website: mirroredgardens.art

WeChat: mirroredgardens

Tel: +86 20-31043759

Mirrored Gardens email contact: mail@mirroredgardens.art