Reflection

Infrastructures, Topography, and Landscapes

Zhou Tao Interview Series I

Zhou Tao (hereinafter referred to as ZT): First there is Nature, a natural landscape. Then, mountainous folds started appearing in infrastructures. I find it a violent conflict. It is not a kind of fiction, just a conflict. It gives the feeling of a wrinkled landscape which is created by human. They are neither the mountains-and-waters

of Nature, nor are they cultivated feelings projected upon the landscape.

It is violent and conflicting; it mercilessly drops the landscape in front of your eyes. This is what I call conflictual topography, a very important motif in my work. The moment I see those men fishing on the lake, it feels like discovering a pillar between the earth and the sky. There are also surreal elements in this imagery, which results from a kind of infrastructural terrain. To me, infrastructure is a set of transformative conditions.

Hu Fang (hereinafter referred to as HF): This kind of transformation does not only operate in one direction—it’s reciprocal. In the film, we are precisely confronted with a kind of spillover effect from the tension generated by infrastructural terrain: the nighttime fishing takes place in the shadows of industrial remains, under the overpass and

in the muck. In the remnants of the New World, men seem

to be redundant. But they also invent forms of self-sufficient entertainment. Infrastructures are built to control and reform, but it cannot regulate the dispersion of life, which always escape the framework of infrastructural planning.

ZT: That’s the hunch of the New World, which lies in the self-sufficiency of the fishing men. Our society has assigned people into categories, in which there are no redundant spaces, no excessive frames, and no extra landscapes. But these surpluses are everywhere and they accumulate when you try to approach with the act of filming, eventually you become part of the landscape. I don’t think they are spectacles, they are all around. In fact, when you are building physical structures, you are also creating the shadows and excessiveness, as well as a kind of possibility. People can find their joys of life here without going to a karaoke every day. I think the fishing men are my heroes in my film. They are pioneers.

HF: At the beginning of the film, you frame the river bank under the bridge like a theater. It is clearly a form of infrastructure,

and a stage for human activities. Image-making is like a kind of topographic distribution, with different geological textures and its corresponding perceptions. When we get to the part of nighttime fishing, I feel that we are entering a thick, viscous zone, which unfolds like shallow depressions in the film.

Video still, Zhou Tao, The Wordly Cave, 2017, Single channel 4K video (color, with sound), 47’53’’

Video still, Zhou Tao, The Wordly Cave, 2017, Single channel 4K video (color, with sound), 47’53’’

ZT: That is the moment to bring forward the shallows, and it won’t deliver the same effect if it is postponed. It gets more surreal after that. I only realized how the terrains were formed after the editing. Together with

the sirens of the rescue scene, the integrity of a locale comes into being. I found consistency in the flows of emotion accommodated by the images.

HF: Here, the pairings of back and forth, up and down have emerged. In an ambiguous process, things move, sites disappear, time travels, and it goes beyond the designated meanings and ends.

ZT: The travelling back and forth can happen within the same spot, it doesn’t have to be from point A to B. This kind of travel is closer to filmic narrative. If we are not dealing with documentary narratives, nor a story with protagonist, then what kind of spatial movement has supported the narrative?

HF: It manifests as forms of recurrence. I think light also plays

an important role in shaping form. It allows terrain to take shape, transcending a single visual experience. It is even internal to how the narrative takes shape. For example, in Blue and Red, the light source is relative clear, meaning that it fully exposes the social origin of such light. But in Fán Dòng (The Wordly Cave), the way in which light molds form is different, in the sense that it no longer relies on a social light source.

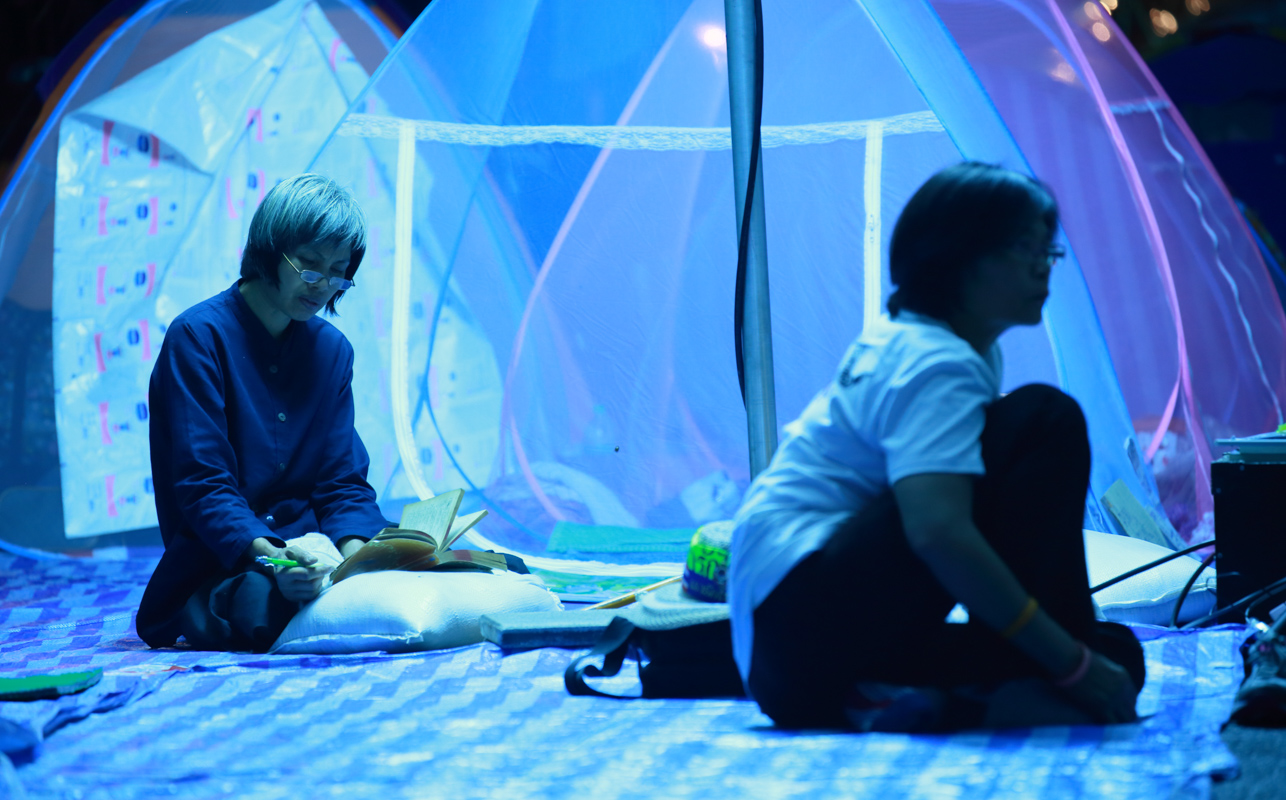

Video still, Zhou Tao, Blue and Red, Single channel HD video (16:9, color, with sound), 25’14’’

Video still, Zhou Tao, Blue and Red, Single channel HD video (16:9, color, with sound), 25’14’’

ZT: Another point, I think the observation perspectives differ in these works. Only in Fán Dòng (The Wordly Cave) does light truly start to shape a terrain and its composition, whereas the light in Red and Blue is immersive like alcohol. Of course, within all this there are subtle changes which are produced between the undulations and have merged with the terrains simultaneously.

HF: Speaking of topography, I am reminded of something Dong Qichang said: “The faraway mountains rise or fall to pick up force, while scattered woods elevate or descend to project emotions. This is the essence of painting.” This is perhaps why the correlation between topography and film holds such an appeal. Rather than making external connections between material compositions, it is about finding a deeper structure of resonances. A site often creates an illusion: a New World seems to come into being, but there are no longer spaces for human to take refuge in. In Fán Dòng (The Wordly Cave), as the terrains unfold, humans are pushed to confront their own existential conundrum.

ZT: In terms of waters-and-mountains painting, I don’t think my films

can be compared to a long scroll that unfolds on one side. Instead, as one side unfolds, the other side closes. You hardly get the whole picture, as the landscape is not represented a panorama. You need to throw your own body into these terrains, so as to feel the softness and hardness and what you would see when you look up…etc. I suppose it is about “being within”.

HF: It doesn’t have to contain a so-called wholeness, since it cannot be seen at one glance. Instead, it has a restrained quality, like when you are about to speak, yet words get caught at the tip of your tongue.

ZT: I think it has to do with this conflict that you speak of. Conflict

might just be a significant mood that ultimately attracts you to interpret and decode a certain topography. This feeling cannot be grasped at one glance. Regarding the formation of point of view, I’m deeply influenced by waters-and-mountains painting and literati poetry. However, I haven’t thought much more about how the languages of Chinese paintings could be transformed to different medium such as film. There are spiritual resonances. What initially drew my attention to the infrastructural mountains that I spoke of earlier, had to do with conflicts and ruptures related to the historical context of Literati Paintings. The waters-and- mountains are not accessible landscapes on paper that people normally think of. By rediscovering the relationship between the body and nature, they project a sense of disruption because Chinese culture went through traumatic changes in the Yuan Dynasty. The Chinese intellectuals were excluded from the political mainstream, and they retreated to observe the meanings of their surrounding environments and started to produce a kind of painting that does not rely on color and technique,

but were imbued with spirits and feelings straight from the heart. Song Dynasty landscapes are also very beautiful, but they don’t have the same implications. Today is also a time of great turmoil, and the challenges are global. It feels thrilling to invoke the concept of landscape, as you have

to throw whatever that makes you uncomfortable in the equation, and

you can’t just lie there and enjoy yourself. You don’t have to own a villa,

a grass hut would be enough. Only with the right frame of mind can we have a future. An easy life does not lead to imagination. Confronted with globalization, what fate lies in store for landscapes in Chinese painting? It’s not that I am borrowing a certain technique or genre, but rather that I am exploring this motif, challenging it and questioning it.

The creation and construction of this topographical narrative is very interesting, and just like what we talked about, there is nothing that can

be taken in all at once, but there also exists a form that could project the existence of another terrain. That’s what films and images try to convey. Of course, sometimes affects can be found between structures, and they are possibly prioritized over physical spaces and structures. Perhaps it is akin to writing. In preserving the structures between different realities, I try to keep contact with a certain realness, then I wait to see how other possibilities unfold. It is hard to be analytical: when you are at the editing table, images start to emerge and become self-constitutive flows.

HF: What’s fascinating here is that the structure of the moving-image itself is already embedded in the topography of reality, which can only appear in our consciousness and be touched upon through your moving-image practice.

Video still, Zhou Tao, Blue and Red, Single channel HD video (16:9, color, with sound), 25’14’’

Video still, Zhou Tao, Blue and Red, Single channel HD video (16:9, color, with sound), 25’14’’

Video still, Zhou Tao, The Wordly Cave, 2017, Single channel 4K video (color, with sound), 47’53’’

Video still, Zhou Tao, The Wordly Cave, 2017, Single channel 4K video (color, with sound), 47’53’’

The conversation took place in Zhou Tao’s studio, Guangzhou, May 2017

Included in Zhou Tao: The Ridge in A Bronze Mirror Guidebook, Times Museum, Guangzhou, 2019, Chinese and English, pp.79-83.

_ _ _

Sometime, when you observe the surroundings and people around you in detail, you will capture those hidden traces that connect with your inner heart. During these moments, you will forget the existence of the physicality of yourself or the subject; only feelings and ideas are flowing. This is precisely the starting point of a fiction. You are the audience. The existence is objectified and becomes a film or a play. This is my description of the perceptive relations. I don’t want it to be considered as merely a viewing concept.

– Zhou Tao

I experienced a certain moment. I found the same experience in Zhou Tao’s videos Collect or After Reality. The videos offer something far more complicated than what I had experienced in reality, yet I can only use myself as a medium through which to describe these works. In this time-space that is not “either-or” but “both-and”, it allows us to create and enter with our own ways. In the “moments” that we have, time is never cut. Therefore, my experience may just set the “depth of field” for viewing Zhou’s videos. When “we” long to surpass the limited time of our existence, our experiences will start to interact with this world.

We are travelling, not through images, but within a “volume of time”. It is only when the threads hidden within time link with our perceptions, at “that moment”, that existence can be revealed. This is why Zhou Tao does not perform (when you perform, you will be blocked by your own performance), but rather he moves. He moves, seemingly unaware of his own movements, as one “does not enter into communication with the outside world except unawares.”¹ He does so in order to throw himself to this vast field of the world, to follow the footsteps of fate, to wait, to urge for the “revealing” of an invisible existence. But to reveal is not the goal. To reveal, but what for? If revealing equals to intervening and distorting the “shelter” where “existence” hides, all it will reflect will merely be our own confusion and desire. After all, since existence is invisible and silenct, humans have to step forwards, transforming their own selves as the media with which to test its depth. Perhaps it is this “moment of unawares” that makes the elegance of human action possible.

– Excerpts from Hu Fang A Place Where the Spirits Rest, appeared on Zhou Tao: The Man Who Eats Pigeons, published by Kadist Art Foundation, Paris, 2013

________________________________________

¹ Robert Bresson, Notes on Cinematography, translated by Jonathan Griffin, Urizen Books, New York, p 51

(All images: Courtesy the artist and Vitamin Creative Space, Text: Vitamin Archive)

Selected Works