Give Me a Pair of Elegant Wings and the Light Contained within Darkness

——“Memos for the Next Millennium” for Yuan Jai

Hu Fang

The array of stars brightens the deep night;

My lit lamp matches the moon above the cliffs.

Shining full like an unpolished gem,

My heart hangs within the ethereal sky.

——Hanshan (Tang Dynasty)

Two things fill the mind with every new and increasing wonder and awe, the oftener and the more steadily I reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.

—— Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

It was a long time before I finally glimpsed those utterances, flying through the sky, scattered on the empty ground. As if a fireworks show had ended, we remained staring into the depths of the once-lit sky. Those who have been fortunate to encounter the world of Yuan Jai’s art may know what I mean: the stunned feeling after a rich banquet for the senses. This feeling is followed by submersion into quiet contemplation, the post-spectacle realm where silence conquers words. And that distant place is the starry sky of culture, so often obscured by the dust of memory and history. These paintings contain an intricate lineage of artists past, but they also strike postures of rebellion. The result is a new vitality within Chinese painting that compels us to ask: what kind of life experience must an artist endure before she enters “the place where the light was waning, where I turned my head and I saw the one I sought, after searching the crowd for him a million times?”[1]

1

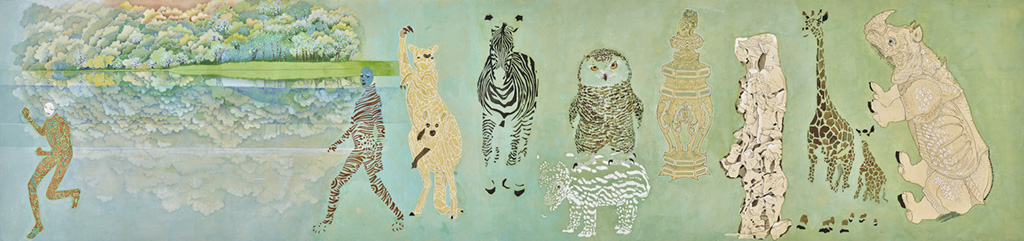

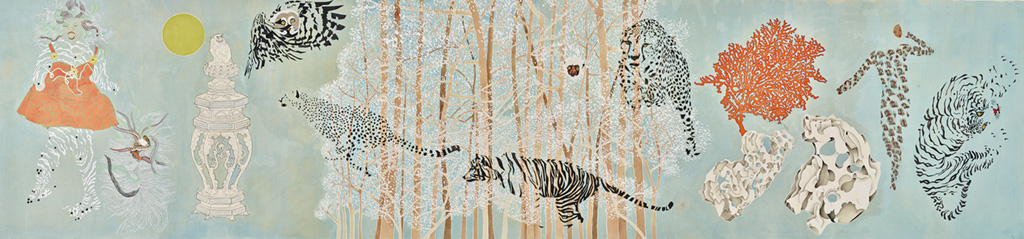

Upon opening the long horizontal scroll of Hazard Path, we seem to see a dramatic re-enactment of the cycle of life. The complexity of the artwork is packaged within a plainness reminiscent of Chinese opera sets: much space left empty, the background a primordial vacuum. The performance begins with a rhinoceros, that ancient and vigorous animal, successively followed by a mother giraffe, a Taihu stone standing on its side, a lamppost carved from stone (an image lifted from Li Gonglin’s Drawing of Vimalakirti Lecturing), an owl, a zebra, a mother kangaroo, and a striped person with a blue face. They lead our gaze toward a stretch of the journey with exquisite scenery: a colorful forest, reflected in the surface of a lake. On its other side, an apparently fleeing person, her entire body covered with oracle-bone inscriptions, including the words “Changsha Yuan Jai”: the hometown that the artist cannot banish from her memory. We sweep past a tiger’s stripes, a fleeting human shadow concealed amid mountain peaks, and blood-red coral that evokes a Zen koan: “every branch of coral holds up the moon”. Then we enter a different forest, a white ape perched in its branches, fleet-footed pumas charging amid the trees, and an owl startled into flight toward the bright moon. When the stone-carved lamppost appears again, the rays of light around it have changed as if with the passing of seasons, marking the ephemerality of time, and we finally encounter the young girl with a brightly colored dress and the body of a leopard. She faces us, dancing wildly, her hair hanging loose, her mouth open as if to shout or sing. Yuan Jai claims that when her granddaughter saw this part, she exclaimed: “grandma’s crazy!”

Yuan Jai, Hazard Path, 2016, ink and colour on silk, hand scroll size: 47 × 396 cm, details

Yuan Jai, Hazard Path, 2016, ink and colour on silk, hand scroll size: 47 × 396 cm, details

(this art work is meant to be viewed from right to left)

Yuan Jai painted Hazard Path in 2016, at the age of seventy-five. Five years before, she had painted Reaching Seventy, a painting that includes an image of herself at the age of five drawn from a photograph. At the time of the photograph, World War II had just ended, and Yuan Jai was still in Chongqing. The photograph shows an innocent girl with no inkling of the great vicissitudes that awaited in China’s destiny. In the painting, the child’s face is transformed into that of an eagle. The girl’s left hand holds her right thumb, forefinger and middle finger—the fingers used to hold a paintbrush—in a portent of her future as an artist. The Taihu stone, stone lion, and stream behind her suggest a garden-like space. A ladder leads upward to an image of the Da He Ding, a massive bronze vessel that was used for important rituals during the Shang Dynasty. However, the male face on the side of the vessel has been transformed into a female visage, her eyes serenely averted, as if she calmly awaits everything that will occur. And the “Double Happiness” character at the top of the ladder seems to corroborate the child’s unwavering connection to art and culture.

Yuan Jai, Reaching Seventy, 2011, ink and colour on silk, 190 × 90 cm

Yuan Jai, Reaching Seventy, 2011, ink and colour on silk, 190 × 90 cm

In order to appreciate these portrayals of the journey of life, we should first allow ourselves to experience an imagined transformation, just as the artist converts the invisible process of spiritual growth into figurative forms that combine human and non-human forces. These forms illustrate what might be called a poetic root-seeking; a journey backward in time; a forging of spiritual sublimity; or a “transcendent response”[2] that traverses space and time. This manner of mental craft, all but lost in contemporary times, allows a reawakening of sensitivity to the connection between all living things. The artworks also offer us a moment of experience that relates to both the past and the present, that recalls T.S. Eliot’s description of “historical sense” that “involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence … this historical sense … is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and of the temporal together.”[3] Thus the historical artefacts and implements that appear in Yuan Jai’s paintings are neither props nor allusions; rather, they are vessels of common cultural memory, waiting for us to encounter them, when they reanimate as vital forces of association.

2

If we trace back what Walter Benjamin said, “the art of storytelling is reaching its end because the epic side of truth, wisdom, is dying out,”[4] then Yuan Jai revives the narrative potential of Chinese painting by continuously positioning the narrative within the relationship between the individual and history. She explores the cultural ecosystem cultivated by individual life experience, thereby developing a series of cultural narratives. Only by locating these narratives within continuous—rather than fragmented—cultural processes can the artist enter into the realm of life philosophy through the composition of a painting. I compare this accomplishment to the creation of a hidden garden: in order to return to this garden, its creator must first leave it, and perhaps even become a stranger to it.

The girl in Wonderland Revisited (2013) seems to be an outsider who is full of wisdom and innocent of seductive connotations. The girl appears to be comprehensively happy, and also devoid of burden, such that she can fully immerse herself in her secret delight. In this garden, inaccessible to others, the source of her present pleasure lies in communion with five thousand years of cultural history—but how does the “perceptibility” of historical facts become accessible to our senses, minds, and hearts?

Yuan Jai, Wonderland Revisited, 2013, ink and colour on silk, 112 × 220 cm

Yuan Jai, Wonderland Revisited, 2013, ink and colour on silk, 112 × 220 cm

The girl invites us to become garden visitors, which involves an overlap of at least three gazes—our perspective, her perspective, and the narrator’s perspective, allowing the space-time of our relative experience to flow without interruption. We encounter a tattooed Taihu stone, a mother rhinoceros, and a reanimated life-force from beneath the earth’s surface: ritual treasures and grave figurines that form part of a celebratory scene of song and dance. Viewed with an innocent perspective, they break free from an excessively mature, rational experience of Chinese history. Instead, they exude playful vitality. Even if we are not particularly familiar with their original cultural context, that does not prevent them from becoming a clever, communally enjoyable human experience, akin to the moments of awe one experiences when reading Alice in Wonderland.

From the series Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (2007) to Amor fati (Love of Fate) (2017), from Garden in the Mirror (2014) to Nature Within (2016), Yuan Jai’s paintings consistently suggest the existence of a garden space, which we can interpret as a response to the modern, exorcised world, violently changing and always accelerating. The paintings extend this sheltering and transformative space to yet broader fields, whether it is the intimacy with the “small beasts” depicted in We Can be Friends (2008) or the homage to the nurturing mother, situated between human and animal, depicted in Mother Earth (2014). In this way, Yuan Jai’s paintings contain explorations of the primeval world in which humans and all other species deserve to live.

Yuan Jai , Nature Within, 2016, a set of two, ink and colour on silk, 203 × 89 cm / each

Yuan Jai , Nature Within, 2016, a set of two, ink and colour on silk, 203 × 89 cm / each

“The earth is full of refugees, human and not, without refuge.” This is how Donna Haraway describes the predicament of contemporary humanity and the planet. “We are facing the production of systemic homelessness. The way that flowers aren’t blooming at the right time, and so insects can’t feed their babies and can’t travel because the timing is all screwed up, is a kind of forced homelessness. It’s a kind of forced migration, in time and space.”[5] The artistic world of Yuan Jai helps us realize that a refuge and homeland possibly exist. Her art inherits the “Shanshui” spirit in the traditional sense, but is no longer limited to depicting a certain concept of natural order within cultural conventions.

3

The striking combination of the bronze bull of Wall Street with the five bulls from the Tang Dynasty painting Five Bulls by Han Huang produces a world of coexisting differences in Charge (2012). In the context of cultural flow and migration, Yuan Jai refuses to rely exclusively on Chinese aesthetics of formal meaning. Instead, she embraces an encyclopedic approach, drawing on resources of folk, imperial, scholarly, minority, family, and personal origin, and transforming them into vessels of cultural narrative by means of her inclusive and comprehensive mastery.

Yuan Jai , Charge, 2012, ink and colour on silk, 133 × 204 cm

Yuan Jai , Charge, 2012, ink and colour on silk, 133 × 204 cm

As Yuan Jai’s paintings express the individual experience as an intense and brilliant visual world, they simultaneously concentrate cultural experience into an analysis of values worthy of communal consideration. The colorful world of birds and fish portrayed in Nature Within, a contemplative landscape of towering mountains and flowing rivers, is an externalization of the artist’s inner garden as well as an alternative expression of the “Yuqiao” [6]ideal—declining a public position in favor of living the simple and secluded life of the fisherman and woodsman—that has appeared in various periods of Chinese history. The bottle that appears in Amor fati (Love of Fate) is more suggestive of a form with the characteristics of quantum space: its emptiness is itself an essential ingredient in creating the form, while also explicitly manifesting “space”. It is an integrated external form and interior that shape and refer to each other in reciprocity. Not only do the bottle’s graceful shape, gentle color, and smooth texture emit a pleasant energy, but also, the word for bottle, píng connotes the word for peace (píng’ān), a homophone. Thus does the “bottle” space contain a message of life sheltered.

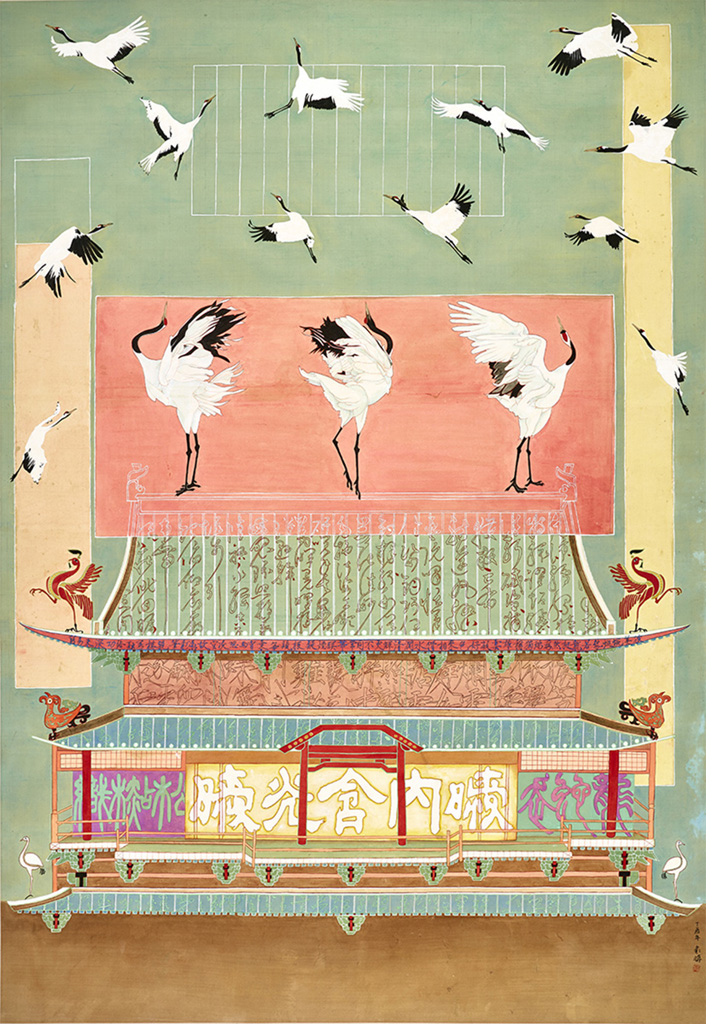

The place that Yuan Jai invites us to enter is a world in which the value of life is reverently protected and cultural dynamism is continuously pursued. In Auspicious Cranes (2017), the words appear on the building are an epigraph from the late Han poet Cui Yuan: “The Light Contained within Darkness,” hinting at Yuan’s interest in the light of morality and virtue. This calls to mind Magnificence (2017), in which the artist attempts to capture the radiance of flame, though its form and void both remain invisible. Yuan Jai adopts an egoless approach to lending form and color to that which is intangible, and allowing vitality to flow therein.

Yuan Jai, Auspicious Cranes, 2017, ink and colour on silk, 171 × 118 cm

Yuan Jai, Auspicious Cranes, 2017, ink and colour on silk, 171 × 118 cm

Thus, in the abstract background of Hazard Path, the objects and animals appear gravity-free, suspended and floating. The stone lamppost calls to mind the spaceship from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, flying toward both the past and the future. The interactive power of the myriad things in Yuan Jai’s paintings lends them a kinship to Walter Benjamin’s “Angel of History.”[7] They express both anxiety and empathy for what has occurred and what will occur. But they do more than observe the tribulations of human experience; they also witness the perpetual continuation of life, and as a consequence, their passage around the earth’s ever-turning axis is calm.

Text © 2020 the Author and The Pavilion

All works of art by Yuan Jai © the Artist

Courtesy of the Artist and Vitamin Creative Space

[1] Xin Qiji, “Qing yu’an – yuan xi,” collected in Wang Guowei, Ren jian ci hua, Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House, Shanghai (1998), p. 6. Chinese.

[2] In Lun zhongguo jishu wenti, Yuk Hui observes: in Chinese cosmology, we find senses other than vision, hearing, and touch. They are referred to as 感应 (gǎnyìng: perception), characters that imply 感觉 (gǎnjué: feeling) and 响应 (xiǎngyìng: response). These perceptions are generally understood as “correlative thinking” … this is not merely the product of subjective contemplation, but rather, something that emerges from the resonance between humans and the heavens, which are the foundation of morality.

[3] T.S. Eliot, “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” Eliot: Collected Works, Wang Enzhong ed., International Culture Press, Beijing (1989), p. 2. Chinese.

[4] Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller,” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, Hannah Arendt ed., Zhang Xudong, Wang Wen trans., Sanlian Press, Beijing (2014), p. 98. Chinese

[5]Donna Haraway, “Post-Truth, Climate Crisis, and New Political Imagination,” The Paper: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_3753029

[6] In ancient Chinese art and poetry, there are numerous descriptions of fishing and wood-cutting as a kind of cultural archetype: Yuqiao–the fisherman and woodsman. These vocations metaphorically represent a life of reclusion for one in whom thought and action are united; this person is also considered to be an objective observer of history.

[7] In 1921, Walter Benjamin purchased Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus at a small art exhibition in Berlin, and kept it for the rest of his life. In chapter nine of “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Benjamin famously discusses the image and meaning of the “angel of history.” In Benjamin’s view, what is important is not the continuum of the past, but rather, the necessity of smashing the continuum of historical time. Then the fragmented objects of history return to life as dialectical images. Benjamin sought more complete meaning through the reconstruction of the fragments of modernity.