Reflection

Tempering The Mortal Body

– Hu Fang in Conversation with Hao Liang

Hu Fang (as Fang below): Shan shui (mountain-water, the natural landscape) in traditional Chinese painting isn’t only a motif but is also presented as a reflection of one’s vision of the universe. Thus the exercise of Chinese painting is in fact a process of the painter’s persistent inquiry into the relationship between himself or herself and the world, and the mutual reflection of the two. When you were in art school, you imitated Travelers Among Mountains and Streams (《溪山行旅图》). I am curious, what were your feelings when you first encountered shan shui? Did the experience constitute a special and inspiring moment in your life?

Hao Liang (as Liang below): Since ancient times, making imitations has always been a fundamental means with which to learn Chinese painting, which is comparable to learning words and classics as the foundation of any academic activities. In Chinese painting, any innovative or ground-breaking act can only be achieved after the painter has learnt thoroughly all the existing artistic legacy.

When I was in my second year in art school, during the shan shui painting class I did imitation exercises with Travelers Among Mountains and Streams by Fan Kuan (范宽) from the Northern Song Dynasty. It was a very interesting process. I began by making imitations of its details, and only after a few practices of its details did I have the courage to imitate the whole painting. After two months of staying up all night working, I finally finished the painting. It was my first attempt to imitate a monumental landscape painting. At that time, most of my effort was spent on making it look like the original, and in retrospect it was pretty much a process of learning the basics. Only after many years was I able to comprehend and digest the true content of the painting. Since then, I have imitated many masterpieces; it was the beginning of my journey to learn from the ancients and the great Nature.

However, it was through the imitation of Travelers Among Mountains and Streams that I started to contemplate a few questions:

1. What is Bimo (the method of brush and ink)? Is the Bimo we advocate today the same as of then?

2. How did Fan Kuan reflect his and the general idea of ‘Nature’ in the Northern Song dynasty through this painting?

3. What is at the root of such imitation exercises?

Then, during a trip to Mount Hua in my fourth year in school, I had an epiphany. It was noon and I was descending the hill. I was exhausted, walking along the paths at the foot of the mountain. The path was shimmering; it was bright. The sunlight came from behind and the mountain was dim. I suddenly realized that in Travelers Among Mountains and Streams what the dark mountain and the bright mountain path represent is a feeling. The spirit of Gewu (“the investigation of things”) was advocated in the Song Dynasty; when it comes to painting, it doesn’t mean portraying things with all the details, but synthesizing complex impressions and emphasizing these. For me, understanding Chinese painting is a gradual process.

Fang: The moment you experienced in Mount Hua is, for me, very touching. The moment travelled across time, not only ascertaining what Fan Kuan “saw” as the law of Nature, but also merging into the shan shui in front of you and that of the historical picture. It happened within an instant, but was fermented through a complicated process. Through learning Chinese painting, you are inspired to converse with the ancients. So, in such a conversation, which aspect is the most crucial? In a dialogue with history, how do you, the “I”, find the position for yourself? Or, from a philosophical point of view, how does the “self” understand his relationship with “the other” in the training of shan shui painting?

Liang: The moment at Mount Hua was very important to me. I can perhaps say that it developed into an “aircraft” of time with which I can travel into the past and the present. In terms of learning classical painting, the stirring moment at Mount Hua was a perfect inspiration, but not the most crucial point. The feeling of “being at the time” made me feel a presence in the landscape, but I must convert and perceive it in terms of the language of painting. What it triggered was a special way to observe; such a way of understanding space and time is a completely different way with that of today. It perhaps explains why the ancients did not pay attention in portraying the objects but emphasized representing the feeling. It is perhaps this that distinguishes shan shui painting with Western landscape painting.

If we can recover the scenery at Mount Hua during high noon, we will be able to do a thorough analysis of Travelers Among Mountains and Streams, and also understand how I obtained the eyes and mind of Fan Kuan. When the sunshine spreads on the pathway, such as the one that the travellers are walking on in the painting, it becomes the brightest thing you can see and it goes into your mind. The mountain with sunlight from behind looks dark, massive and convoluted. In illusionistic landscape depiction, this contre-jour of the mountain will be presented as a whole block but look blurry; contrary to this, mingled with his impressions of the different textures of the mountain rock, Fan Kuan’s mountain was rough, irregular, but complete, formed with a special texture method which creates wrinkles like beans or raindrops. In a shan shui painting that is made according to your feeling (rather than visual memory), places that give you deep impressions will naturally be enlarged and brightened; meanwhile, no place in this painting looks ambiguous, because this shan shui is not only about the object that you observe, but is also a reflection of your mind.

In fact, a large proportion of the painting language created by the classical masters was condensed from their extremely sensitive perception of the external world. Through these paintings, one can imagine the rich and extraordinary vision they had of the world. Of course, I can’t be sure that if such perceptive and way of working only belongs to the ancient Chinese, because my knowledge and experiences are limited.

Fang: The moment that you are sharing is deeply fascinating. And your recovery of the moment has once again become a reflection of your inner mind. It reveals the particularly unique and mysterious time-space dimension of a shan shui painting. So, how do you understand the fundamental changes in your perception of the world brought by the process of learning Chinese painting? In this process of condensation, what is the function of the body? How does the body act as a medium of inheriting and remembering, to feel the things that cannot be conveyed by rational knowledge?

Liang: It is exactly as you said. In the process of learning classical Chinese painting, the pathway to know the objective world has been reopened for me. The way we relate to the world is basically based on convention or habit. We only learn about the world through the flat and unvaried images that we obtain through our retina, not to mention knowing to perceive things with our body. In ancient China, the world was understood in an entirely different way than it is now, when an individual man did not stand at its centre but was only one aspect of the world. This view formed the basis for its unique and splendid art and literature. But one should also note that the development of art and literature has been pretty dismal since the establishment of the PRC. The changes happening among ourselves have made us forget where we came from and where we are going. We’ve become just like the Monkey King.

Learning about classical painting and observing nature made me slowly get to the formation process and the internal logic of these images. It gave me a deeper and more sophisticated understanding of time and space in the picture. Such a becoming is established on the foundation of a personal perception and vision of the world. The coordination between the mind, the hand and the eye takes a long time of learning and training. The painter Cheng Zhengkui (程正揆) from the Ming Dynasty made 500 scrolls of Dream Journey among Stream and Mountains (《江山卧游图》). ‘Dream journey’ actually means visualizing nature through one’s imagination, but such a journey of perceiving and imagining is so long. In the traditional way of learning, after learning from the ancients and nature, one has to eventually learn to convey the mind by the hand, to express the will through the images of things, and to use painting as a medium to represent one’s unique vision of the world.

Fang: Dream Journey Among Stream and Mountains opens our imagination of traveling in dreams. Shan shui painting emphasizes the flexible shifting of perspective. In your works such as The Flourishing and Withering in Four Seasons (《四时荣枯》), Contemplate Shanshui-Sunlight After Snowfall (《看山水——快雪时晴》), The Tale of Cloud (《云记》) and the recent Fire and Water (《水火不容》), one can see that your exploration of perspective is constantly evolving. How did you start this exploration around perspective? Another fundamental question is: why has Chinese painting developed an entirely different “sense of perspective” than Western landscape painting?

The Flourishing and Withering in Four Seasons (close up)

The Flourishing and Withering in Four Seasons,2012,Ink and color on silk, Handscroll, painting size: 46 x 410cm, scroll size: 47 x 750cm

Contemplate Shanshui-Sunlight After Snowfall, 2012, Four hand scrolls, Ink and color on silk, 100 x 45 cm / each painting

Liang: My earliest works are figure paintings, in which shan shui was used as a background. However, I soon realized that practicing shan shui painting would help me to understand more accurately the core of Chinese painting. I first used hand scrolls as a medium to discuss issues of time and space in The Flourishing and Withering in Four Seasons, in which the narrative develops in four seasons to address different things, such as the colours and violence of spring and the monsters and mysteries of summer. When making Contemplate Shanshui-Sunlight After Snowfall, inspired by Study Of Mount Qixia (《栖霞山图》) by the Ming Dynasty painter Zhang Hong (张宏), I realized that the main point is to study form and space. A lofty view of the landscape is created by the sense of form, and a profound aesthetic perspective is the content per se. In The Tale of Cloud, the narrative is led by the subjective perception, breaking away from the usual practice of linear narrative, shifting the focus from natural space to the space in the human body. In my recent piece Fire and Water, narrative elements were reduced, and the motif of two extremes was used to discuss the folds of space and the disposition of time. It goes back to the concept of the universe of shan shui painting. Then I found that the reason behind the huge difference between Chinese shan shui painting and Western landscape painting is that there are different concepts of the universe. The ideal of shan shui painting is the unity of man and nature. It seeks for a relationship between the human body and nature that enhances each other. While in western landscape painting, the emphasis is in observing and dominating nature.

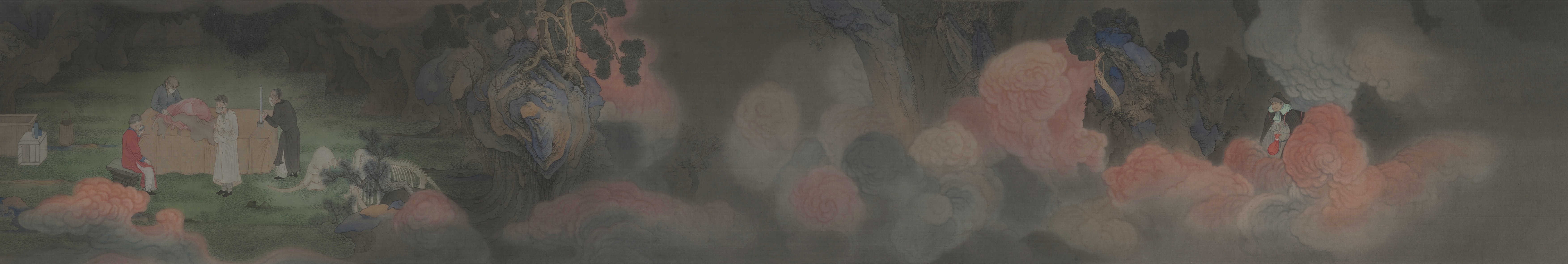

Fire and Water

2014

Ink and colour on silk scroll,

colophon on silk mounting by

Bai Qianshen with three seals

65 x 1130cm,

66 x 1560cm (mounted size)

Fang: The commonalities and differences between Chinese shan shui painting and Western landscape painting is indeed an historical topic. I’d like to slightly move away from it, and ask another question — in today’s situation, do moving images, including contemporary cinema and video art, have an important influence on you, especially in your search for a different perspective that we’ve just discussed? Today, moving images as “simulation of the real” have become the skin of reality. Handy cameras, smartphones, the Internet and other applications that create images in everyday life, have made the shooting of photos and film an internalized part in our consciousness. As a result, images are also gradually internalized as part of our perception system.

Liang: Your question addresses a crucial issue of ink painting, that is, the contemporaneity of it. If you become too obsessed with traditional painting, you will easily get lost as if you’re in a gigantic maze, and be blocked away from many things that are happening now. This is the most perplexing issue in the contemporary practice of ink and wash painting. Meanwhile, one should consider another question, which is how to adjust to things in the outside world (such as the art of moving images that you mentioned) without going too far and losing the original essence of ink and wash painting. I pay a lot of attention to the specificity of moving image art and its recent influences on painting. I pay special attention to the moving image art in the East, tracing its development from Fei Mu (费穆) to Yang Fudong (杨福东), whose works have an entwining and dense narrative style that touches me deeply; on the other hand, the video works about everyday activities by Japanese artist Koki Tanaka remind me of Haiku poetry. In a similar way, I found that the special sense of space in the art of moving images can be combined with that of traditional Chinese hand scroll painting. Therefore, the sense of space that I had in mind when I was painting The Tale of Cloud is very different from the classical painters. In the more recent work Fire and Water I further explored this possibility. Another obvious influence that moving images have on painting is the ambiguity of images, because we are uncertain about what happens before and after the moment that the image represents. In this sense, if I borrow the method of image-making to do my painting, I will gradually move away from the essence of Chinese painting. However, I found that in the prints from the Ming Dynasty, there was a similar technique of expression. In the full version of The Plum in the Golden Vase (《金瓶梅》), there is one illustration for each chapter, but the illustration does not necessary depict the time and the place that the story takes place in. With such an example, one would discovery that the aesthetic of “leaving a distance” in traditional Chinese painting can be inter-referenced with certain aspects in contemporary art. Another example is that in traditional painting, interaction between figures is often represented in an abstract way, and thus the painting is not an illusionistic representation, but the presentation of a ritualized narrative.

Fang: Besides moving images, we must also talk about literature. The first work of yours that I saw was The Path to the Nest of Spiders, a painting named after the novel by Italo Calvino. In this painting, the “negative form” of life as shadows co-exists with the actual bodies, creating a rich sense of the imagination. In your two volumes of “Records of searching for the uncanny,” ancient anecdotal novels became the source of materials to remould. In your remoulding of anecdotal novels, the intersections of virtual time and space and the overlapping of legend and reality seem to have created a comparable pleasure as the carefree travels in the world of semiology and anthropology in Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies and Invisible Cities. Just like in Invisible Cities, the writer told us, through Marco Polo, ‘travel for the sake of returning to your past and seeking for your future.’ What is the connection between your interests in literature and your painting practice? How do you convert the narrative of words to the language of painting?

The Path to the Nest of Spider, 2011, Ink and colour on silk, 80 x 170cm

Liang: Indeed, you and I got to know about each other because of The Path to the Nest of Spiders. I still remember that occasion and our delightful conversation about literature and painting, which we have continued to talk about after that time, as it is related to our practices. Your writings are influenced by visual art, and my paintings are influenced by literature.

Before attending art school, I mostly read the common classics, only later did I start to learn about Modernist novelists like Franz Kafka, Italo Calvino, Albert Camus, Jorge Luis Borges and Orhan Pamuk. Calvino’s Our Ancestors had a great influence on me, in that the figures with only skin and bone that I drew were from it. It may be right to say that my exploration of contemporaneity in ink painting originated from the inspiration from literature. For example, the discussions of history, emptiness, humanity and symbol in Invisible Cities sparked my imagination. I don’t wish to make illustrations for literary works, but rather, like in my painting The Path to the Nest of Spiders, to paint the feelings triggered by stories of the Second World War and guerrilla fights. I’d like my painting to keep an obscure relationship with books. The inspiration of literature has made me believe that there are still a lot of possibilities in traditional ink and wash painting, and I made quite a few works that are related to literature.

In recent years, I have become very obsessed with ancient anecdotal books, because by reading these books I can experience various complex visions of the world, and learn to perceive reality in more different aspects. For example, Night Sailing Ferry (《夜航船》) by Ming Dynasty writer Zhang Dai (张岱) talks about a kind of geography that is completely different from the geography that we know today. Also, one can find some peculiar methodologies in these anecdotal books. Dispersed Records of the Immortal from the Cloud (《云仙散录》) by Feng Zhi (冯贽)from the later Tang Dynasty is a compilation of short essays that can be used to make poetry, and I imitated its style to paint a series of album leaves about time. Paintings expand the space of the imagination provided by the personalized worlds of these anecdotal books. These discoveries and practices have brought me huge pleasure, and showed me the possibility of traveling across different eras.

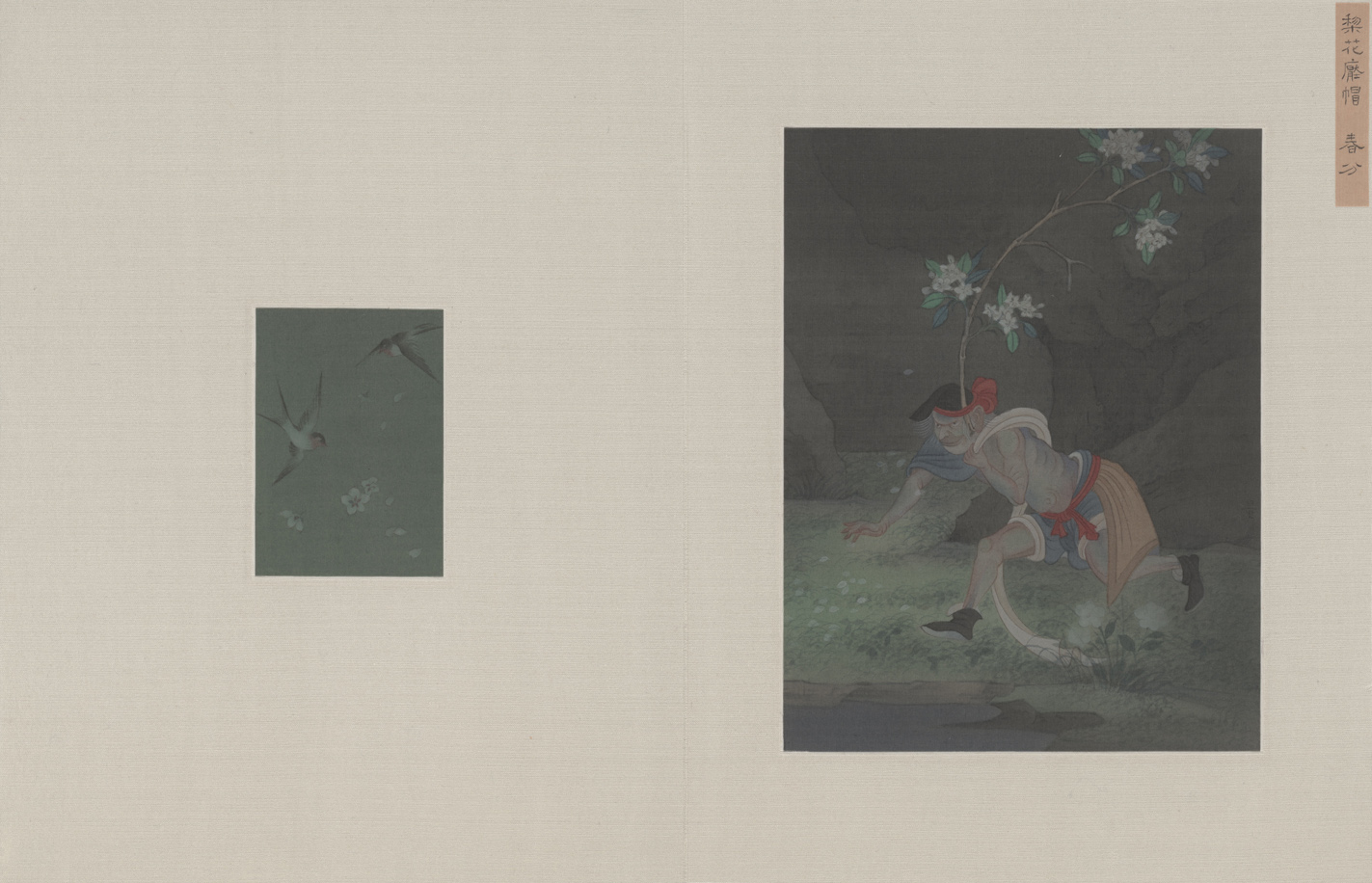

Searching the Wonders – Miscellanea on Leisurely Survival

Pear Blossom Branch as Hairpin Overloads the Head – Vernal Equinox

Searching the Wonders – Miscellanea on Leisurely Survival, 2013, 8 Ink and color on silk, 2custom-made tables, the painting on the left : 9.5×6.5 cm, the painting on the right : 22×17 cm / each album

Fang: In your painting method, besides Chinese painting, there are also influences from miniature painting, Japanese painting and even Flanders painting. The special narrative aesthetics of miniature painting seem to be related to your interest in the narrative of anecdotal novels. Today, there seem to be a potential of merging all kinds of painting styles. How do you think these traditional painting styles can relate to other styles and their own contemporary existence?

Liang: Talking about absorbing and learning from different forms of art, we should discuss the basic pattern of how classical ink and wash painting developed and evolved. The ancient Chinese had the tradition of going back to the old ways, and by going back to the old ways, new theories and ideas were created. Zhao Mengfu (赵孟頫) and Qian Xuan (钱选) went back to the styles of the Tang, Chen Hongshou (陈洪绶 )and Gong Xian (龚贤) went back to the styles of the Five Dynasties and Northern Song, and the Four Wangs (四王)went back to the styles of Yuan — they all inherited styles from a much earlier era so as to balance and refresh their current situations. Not a single era in history can be compared to this era that we are currently in, in the sense that we have now access to a lot of information. When I need stimulation, I can go back to early sources, such as miniature painting. In fact, miniature painting has always had an influence in Chinese painting. Its major subject matters include holy scriptures, religious issues and stories about the emperors, but it is not illustration, which makes it very similar to Chinese printmaking from the Ming Dynasty. Moreover, as you said, miniature painting has a bizarre taste that is in many ways similar to the anecdotal books from the Ming and Qing Dynasties. In this aspect, it gave me a huge amount of inspiration. Other forms of art such as ceramics, woodcarving, Japanese painting, Flanders painting and Fresco have also influenced me. I enjoy such a diverse way of learning, but it takes a long period of practicing to find the best way to use the mixed influences.

Fang: What made today’s environment for making ink and wash painting so different from the ancient times? For example, The Tale of Cloud reflects your insights about the relationship between science and alchemy, that is, how witchcraft and divination can be the origin of modern rationality. I see in it the boundary between rationality and madness created by the modernity project, and it is the existence of the seeds of mutation (like those in anecdotal novels) and madness that is making the crossing of times become possible. What I’d like to understand better is how is the crossing from the external space (nature landscape) to the internal space (human body) in The Tale of Cloud relates to your living conditions in contemporary time? If so, what is the key challenge?

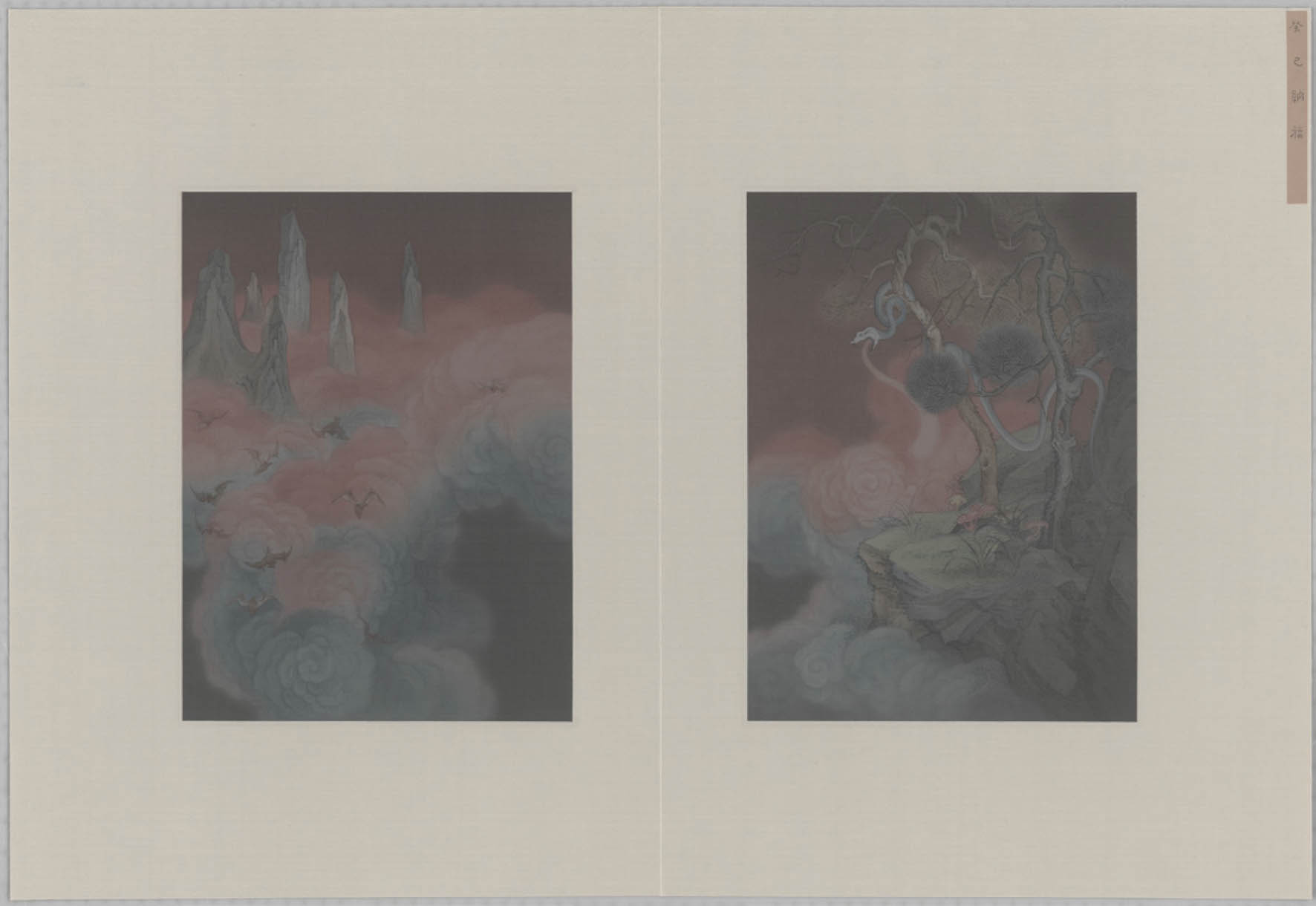

The Tale of Cloud (close up)

The Tale of Cloud, 2013, Ink on silk, 45 x 1200cm

Liang: The changes taking place in our reality and living environment indeed leads to a lot of questioning and contemplating. The remoulding of the natural landscape will not destroy the physical and material forms of mountains, tress and streams, but their relations and conditions have been altered. While the scientific revolution were gradually opening the gate to the modern age, we were also losing the ability to perceive the world with our body. Conventions were established. It is the greatest tragedy of man’s individual existence. I always concern on our scientific way of living, thus in The Tale of Cloud I illustrate a conversion of space to make the body more enormous than the external world. In fact, it represents my suspicions of the scientific spirit. Luckily, I have ink and wash painting, a non-scientific medium, to express my emotions. It brings me closer to the ancients, and it tempers my mortal body. Because of my interest and my profession I have more questions about science and modernity. For example, the reformation of ink and wash painting after the May Forth Movement in 1919 dragged the art form down from heaven; it was no longer noble and profound, and it no longer belonged to the traditional“ritual and music” system. All of these have given us enough reason and motivation to reflect on its current situation. Meanwhile the specificity of ink and wash painting helps me to keep a distance while observing reality.

Fang: It is very interesting that you say it tempers your mortal body, because in this way ink painting becomes the meridian channels and blood vessels of the painter. We have been discussing how the human body can be trained as a medium to inherit and remember and thus to explore the unknown. I feel that within the close relationship between shan shui painting and human perception, there are a lot of subtle details that cannot be generalized and simplified as “concept” and “method”. From your point of view, how does ink and wash painting use its specific way of perceiving to exceed the boundaries given by its era?

Liang: When we talk about ink and washing painting, we should eventually pay attention to its specificity. In fact, the metaphysical nature of its aesthetics has determined its realm and complexity. Let’s use traditional hand scroll painting as an example. Rhythm defines this form. Through material space and musical sense, it creates a unique spectacle. Meanwhile, its vision can only be touched through the painter’s body. The inner nature of ink and wash painting has determined its abstract subject matter. Now, many people catch at the shadow and lose the substance, thus wander away from the core. Since the modern period, in many paintings, the amusement disappeared and only a bare form remained. The problem lies in humans. The weakening of perception is fatal. In my opinion, today, ink and wash painting is traumatized and dispirited.

Fang: If we draw our temporary conclusion with such a comment, what we see is perhaps a realistic picture. From the great contemporary calligrapher Tsang Tsou Choi (曾灶财), we see the same tragic destiny – the real spirit of calligraphy is disappearing in the laws and orders of “normal” society and the market. In Madness and Civilization, Foucault dedicated himself to investigating the relationship between madness and civilized society. In the history of Chinese painting, there are a lot of celebrations for the “noble fools”, such as Xu Wei (徐渭), Bada Shanren (八大山人), Jin Nong(金农)ect.. In the “prototype of the future society” that shan shui painting longs for, there is a resistance of the desires for material wealth. If we realize that shan shui painting has lost its spirit, we must also reflect on our own position in history and our relations with others, and by living with the great tradition of shan shui painting, we probably could find our way to re-settle our life in today’s world and cope with our destiny.

Between December 2013 and January 2014

The Good Fortune of Guǐ Sì (2013, The Year of the Snake), 2013, Ink and color on silk, Single album of painting, 40.5×30.5cm/each painting

(All images: Courtesy the artist and Vitamin Creative Space, Text: Vitamin Archive)