HONGXIA

Cao Fei

‘Even before I learned the movie theatre’s name, a simple desire ashed through me: one day, at this theatre, I will shoot my own movie.’

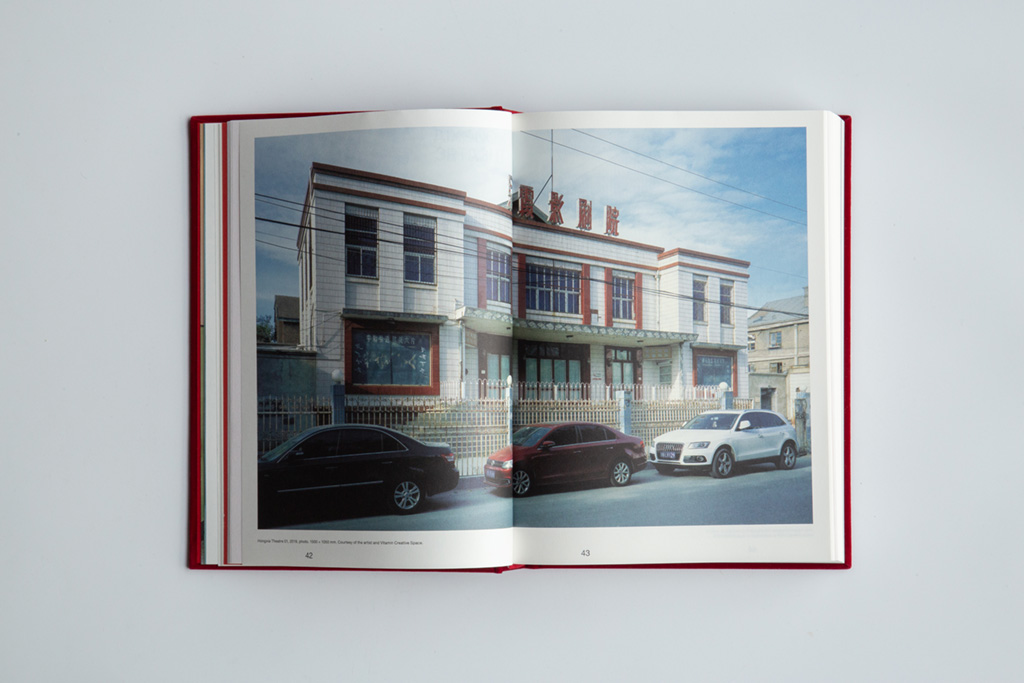

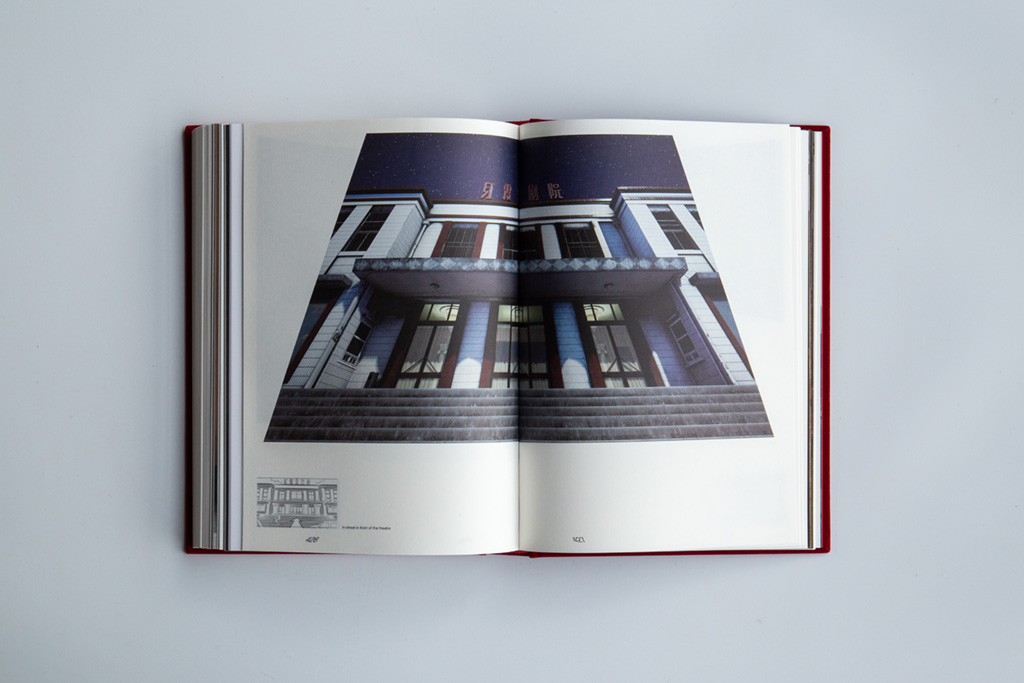

# I was pregnant in the spring of 2011, this time with my daughter, who is now eight years old. At the time, I was scouting for a new work, East Wind, by driving around the outer reaches of the city, looking for exterior locations. In order to avoid the traffic on the East Fourth Ring Road, I turned onto a parallel street, Hongxia Road, which in English literally translates to Rising Dawn Road. Hongxia Road was narrow and somewhat secluded. It was lined on both sides by three-storey, Soviet-style domicile buildings, and I felt as if I had fallen down a hole into the previous century. Then, to my surprise, I happened upon a defunct theatre. It seemed like one of those places where bored young people in county towns go to play and forget themselves in Jia Zhangke movies like Xiao Wu and Platform. It also exuded the nostalgia for youthful radiance of Jiang Wen’s In the Heat of the Sun. I was stunned by how this theatre was frozen in history. It was a typical danwei-style building, tall in the centre with shorter wings and a wide set of stairs leading up to the front door that projected symmetry, order and a sense of ceremony. The faded red and white bricks of the facade set off the five big characters on the roof, their red paint chipping, reading ‘Hongxia Theatre’. The two black and green billboards on each side of the entrance still displayed the faded remnants of old movie posters. The place seemed like a person with a story to tell, its head held high, unable to hide its self-regard. Even before I learned the movie thea- tre’s name, a simple desire ashed through me: one day, at this theatre, I would shoot my own movie.

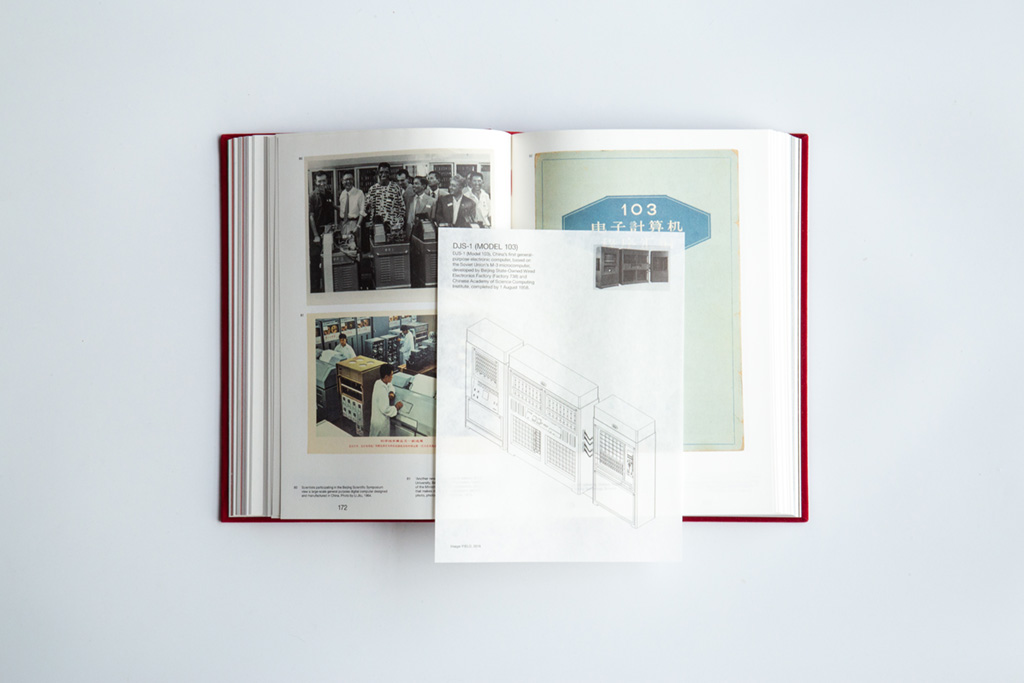

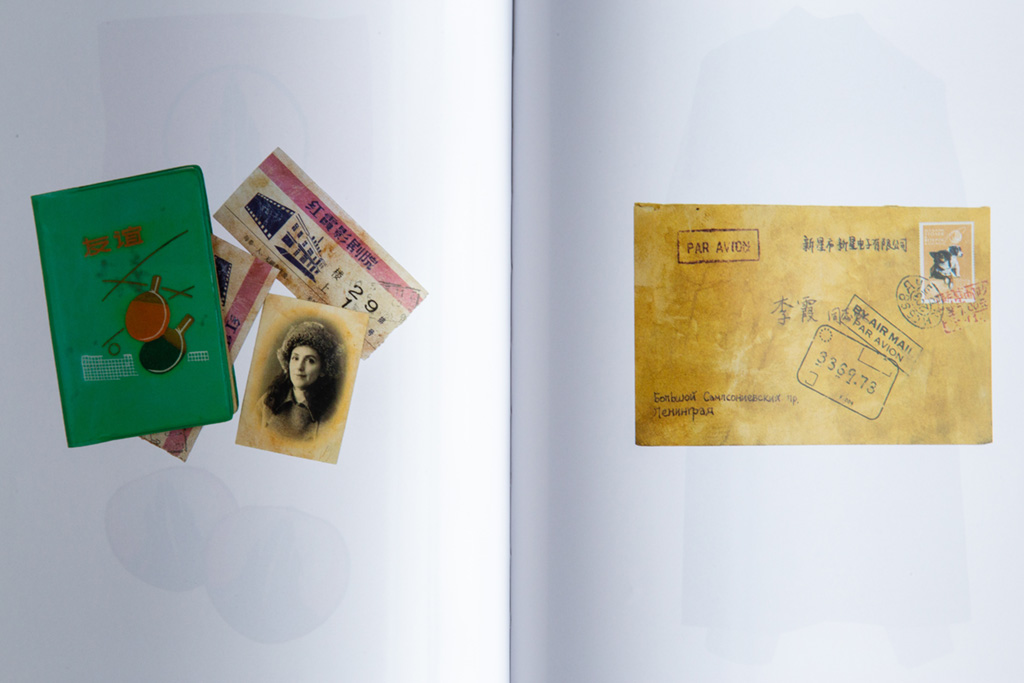

# In ‘Forward Progress at the Electronics Factory’, a history of the Beijing State-Owned Electronics Factory (State-Owned Factory 738) written in 1992, it is mentioned that the Hongxia Theatre was originally a worker mess hall that was not converted into a theatre until 1963. ‘National Survey of One Hundred Large and Medium-sized Enterprises—Beijing Electronics Factory’, published in 1994, states that the theatre was once named ‘The Hongxia Club’, and that, in addition to showing films, it also hosted large meetings and performances around the holidays, including performances by the ‘Hongxia Workers Troupe’, made up of Factory 738 workers…State-Owned Electronics Factory (State-Owned Factory 738), the work unit behind the Hongxia Theatre, Beijing was established in 1957. It was one of 156 important engineering projects that the Soviet Union helped China build during the period of the first Five-Year Plan. The factory’s most glorious achievements were the development and production of China’s first automatic telephone switchboard, first vacuum-tube computer, first transistor computer, first large-size computer to pass one million operations per second and first Great Wall 0500-series personal computer.

# To this day, I often ponder the good fortune that led me to the Hongxia Theatre. If buildings have souls, then was our meeting destined long ago? Was the theatre waiting for someone to come write the story that it could not tell by itself? Silent and ghostly, a building that people had dubbed a ‘living antique’ – what would have happened if it had fallen into the hands of a cultural company, or been turned into a seafood restaurant, a trendy cafe or a courier service? I cannot say for sure which would be best for it, but I do believe that what happened was not random. Rather, we were guided by fate, which al- lowed us to slip into the cracks of time, to face the past and to reassemble its fragmented present.

# In botany, there is a term, ‘false life’, that describes a plant that has died but still contains nutrients that allow the branches and leaves to take root and sprout, or in other words, to exhibit the signs of life. In Jiuxianqiao, there are several withered stumps of trees that have been cut down but still grow new branches each spring. Google Maps describes the Hongxia Theatre as ‘Permanently Closed’, and it’s true that it ceased operating years ago. But then we quietly showed up, we enacted our own botanical ‘false life’, extending the term of the aging theatre.

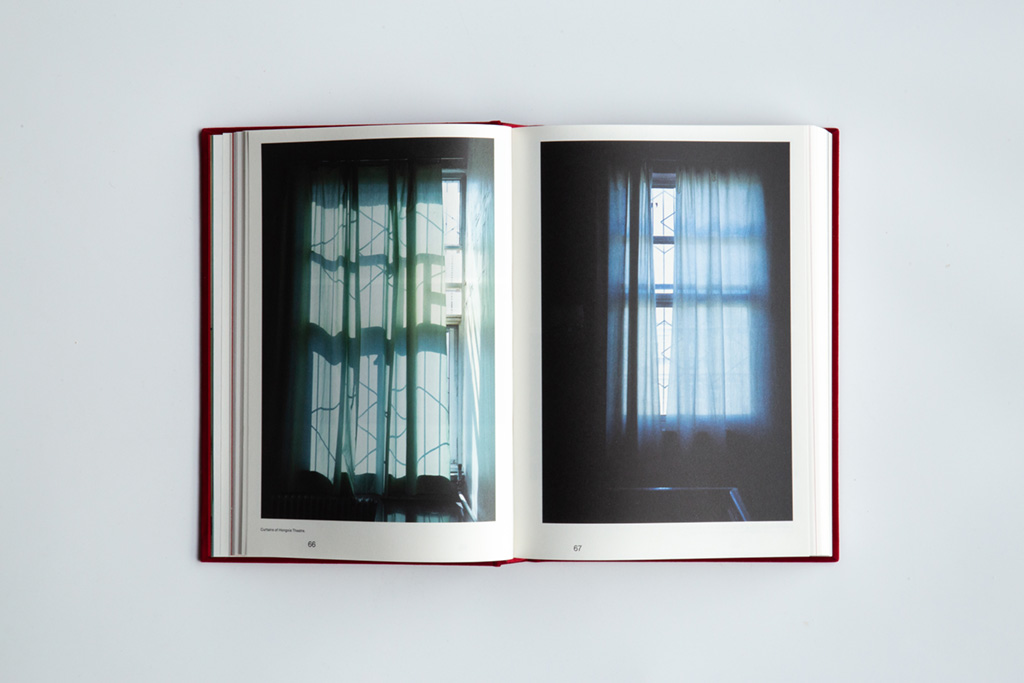

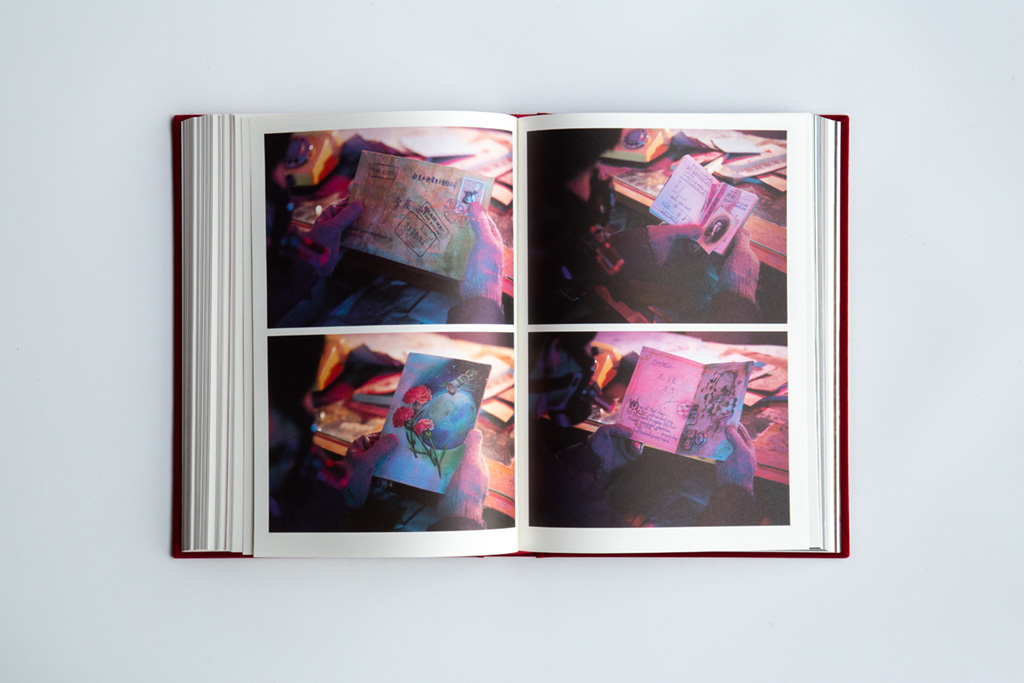

I walked through the theatre countless times, staring into every corner. It became familiar to me in a particular way: I hadn’t grown up here, so it enticed my imagination of an invisible past. And the past was a direction that I had never before explored in my creative work.

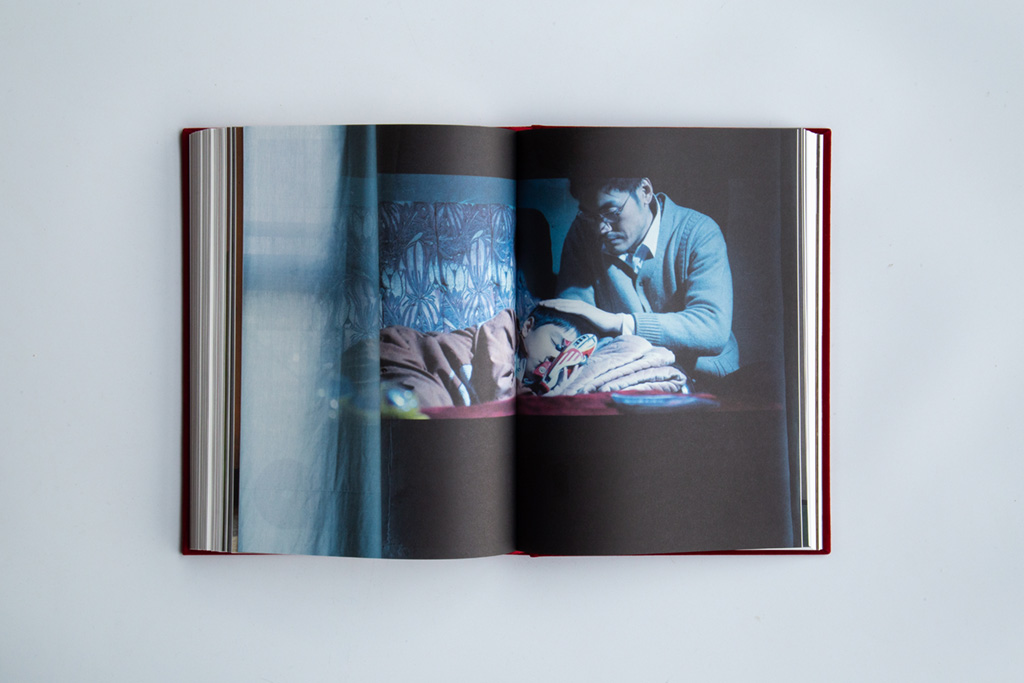

After the film, men, women, children and the elderly press forth out of the screening room. It is already dark outside, and the wall sconces, which symbolise Sino-Soviet friendship, emit a dim light. Black, white and even military-style cloth shoes descend the dark red staircase. Hands of all sizes glide down the handrail as people spiritedly debate the movie that just ended. Children with sleepy expressions, tittering young sweethearts – one by one, they seep into the walls. The surfaces of buildings have memories, and they reflect for us those days in the heat of the sun.

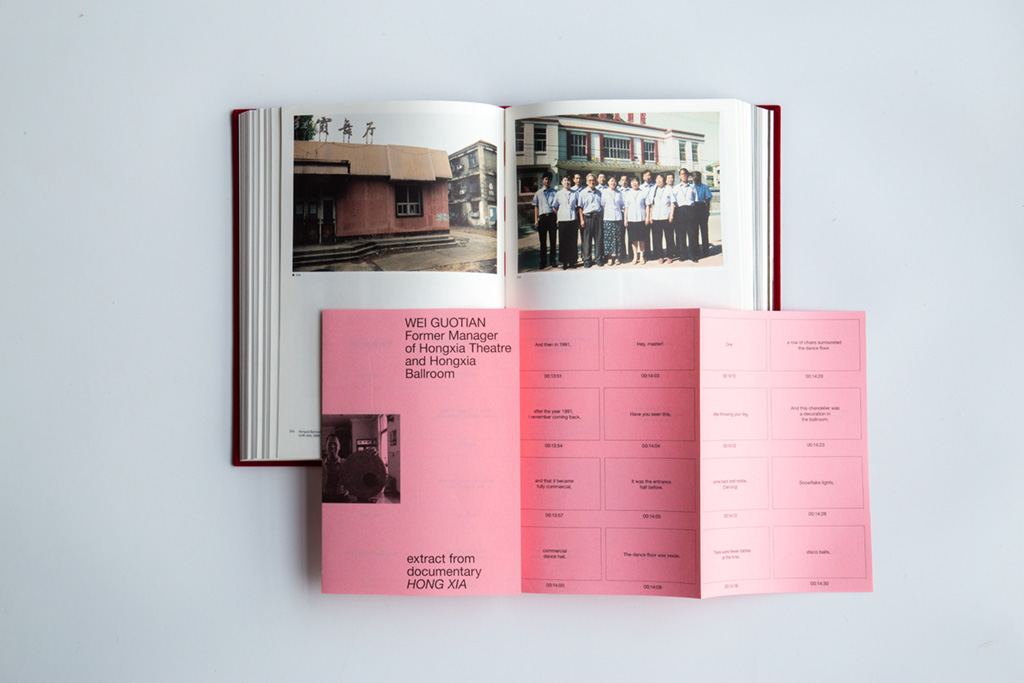

# Many of the residents of Jiuxianqiao had strong feelings about the Hongxia Theatre, which at various times had brought them happiness, joy, grief and pain. They had seen its rise and fall with their own eyes, and the arc of its trajectory reflected the ups and downs of their life stories. Perhaps, as outsiders, we were more capable of looking past the intimacy and baggage that people associated with the place; we had the objectivity required to explore the complex historical role of the theatre itself.

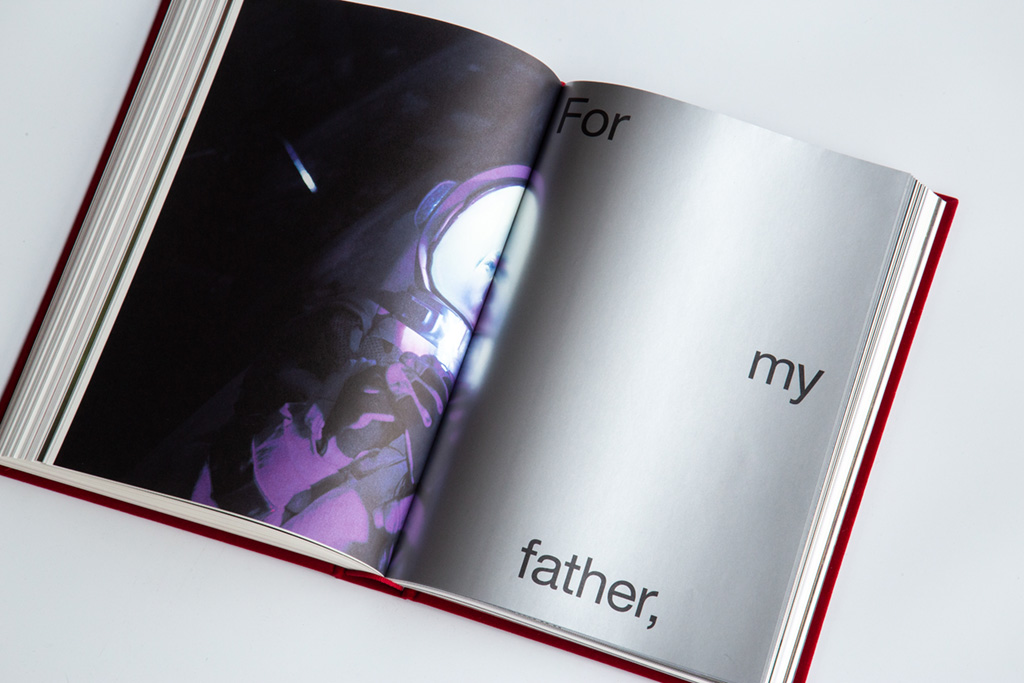

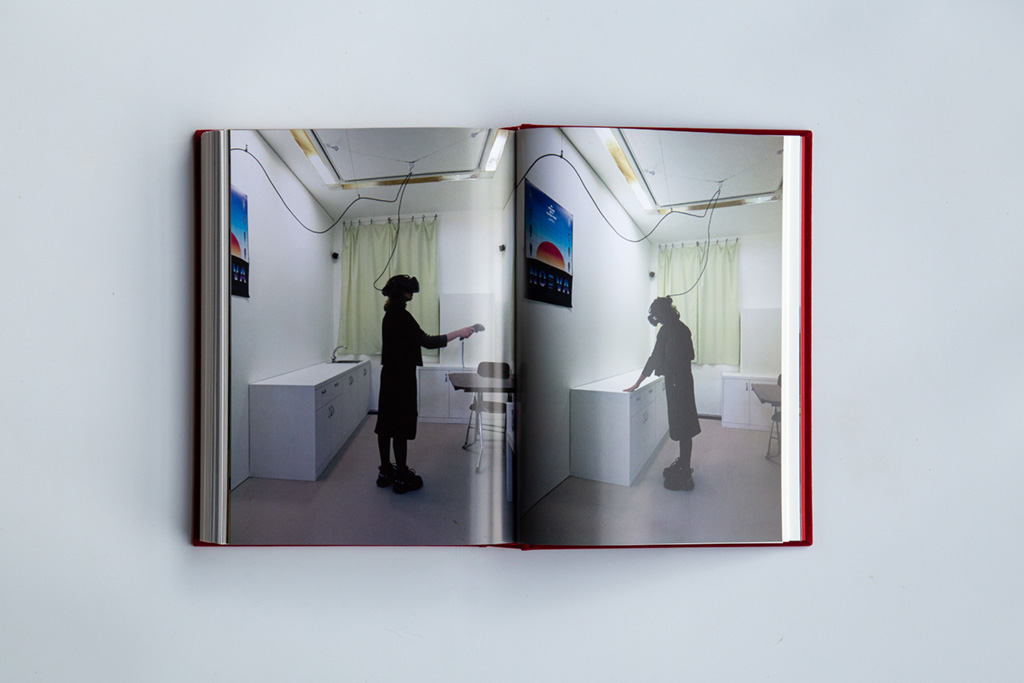

# For four years, the Hongxia Theatre served as a massive bunker: its sturdy shell protected us as we traced time and space backwards. Its intense magnetic field drew us into a temporal black hole. At first, we were spies; then, we became explorers; finally, we evolved into underground workers. We pored over the cruel chapters of history, but no matter how deeply we delved, it seemed that we could never overtake this train travelling in reverse. No matter what we said, we could not encompass its entirety. If Nova, the film we shot here, could be called a requiem to the Hongxia Theatre, then I hope that its clumsy metaphors, coarse poetics, excessive emoting, symbolism and romanticism are capable of delivering our respects to the wandering electrons that have oated through this space, unable to disperse, for so much time.

# We have nobody to report to, and our work was not commissioned by anybody. It does not concern responsibility or obligation, nor is it a righteous appeal for the preservation of industrial heritage. On the first day that I arrived at the Hongxia Theatre, I promised to this place that, no matter what, I would use an alternative means of documentation to preserve its legacy. Today, there’s nothing worth worrying about or regretting. Everything is there.

Thank you, Hongxia, and everyone who ever loved and supported it.

We will no longer fear the arrival of the day of farewell.

Because you have already achieved immortality.

– Excerpts from Cao Fei: “HONGXIA”, In Cao Fei: HX. Beijing: The Pavilion, London: Serpentine Galleries, English, 2020. pp. 25-40.

Text © 2020 the Author and The Pavilion

Photo by Wen Peng

Courtesy of The Pavilion