Liminal Spaces: The Perch of the Ineffable

Up here

Out back

Drink deep

That black light.[1]

——Gary Snyder

Foreword

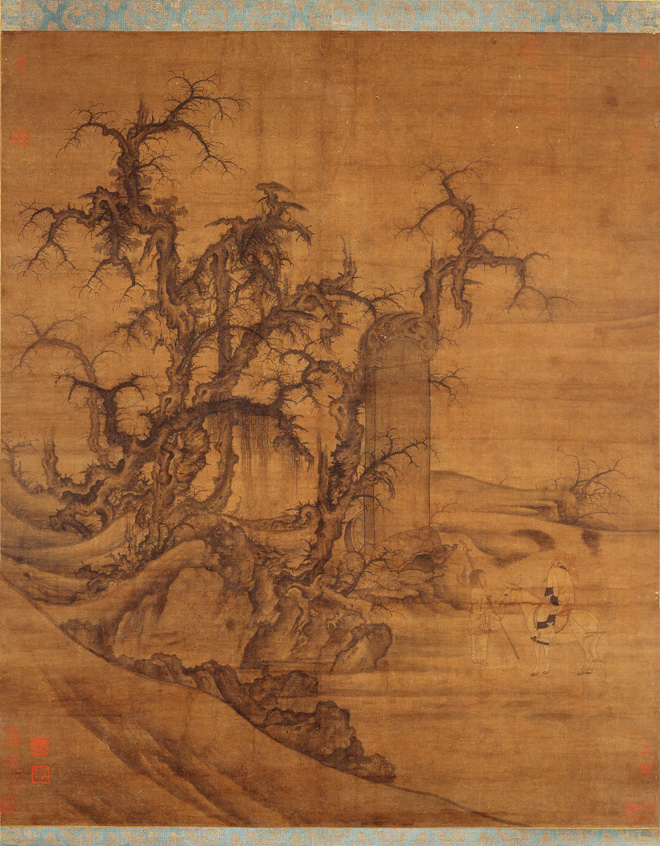

Withered branches stretch like crab claws toward the dark grey skies. They seem to proclaim connotations of hopelessness—yet I am still too young to read and understand the language they write.

I feel the oppressive force of the wind as it rips around the edges of the straw hat pressed tightly onto my head. My servant, his walking stick in his hand, shields his face from the forceful gale. My horse ducks its head and narrows its eyes. Its forelegs seem to tremble. I press my calves more tightly into its belly, where I feel the warmth of its body and a hint of faith in our way forward. In this halting way, we gradually approach a massive stone stele, surrounded by scattered stones and boulders, hidden behind a thicket of ominous trees. The sky grows darker, and a sense of dread fills my heart.

I expected the stele to be covered in inscriptions: something to justify its upright presence in this desolate wilderness. This unusual place surely has some ancient explanation. I didn’t imagine that the stele’s surface would be devoid of any writing, and yet thus it rises before me, blurry and indistinct in the silent, spreading dusk. My perplexed servant strikes the rock with his stick, then stares at this blank slate with his mouth agape. The longer we stare at it, the more it seems that its blank surface is filled with stunning information.

A stray ray of evening light pierces the murky clouds like a first breath of fresh air after an illness. It illuminates faint markings on the stele, then vanishes as quickly as it came. Has time worn away the stele’s inscription, or was there never one in the first place? As I journey through the mountains, I only need one line for me to follow, one brushstroke to remind me that within this vast silence there is still a Heaven above me, still souls on this earth. As evening closes in, the stele glimmers faintly like a bronze mirror. I press my hands to its surface, slowly beginning to feel the bitter cold it contains—and I’m shocked to see that the warmth of my hands leaves traces on its surface, like faint ripples on a calm pond. Snow Cloud, my horse, brays impatiently, urging me to quickly depart this place.

Li Cheng and Wang Xiao, Reading the Memorial Stele, Northern Song Dynasty,

ink on paper, 126.3 × 104.9 cm, collection of Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts.

Permit me to draw on my impressions of Reading the Memorial Stele in an attempt to describe the sensation of encountering the paintings of Yu Han[2]. I do not intend to make a comparison, but if we must seek reference points for our experiences, then perhaps this painted scroll from the Northern Song Dynasty can offer some borrowed context for Yu Han’s work. I often recall this adage: “a printed word is still a word, but a printed painting is not a painting.”[3] As I see it, it is precisely this kind of circumstance that reveals the interchangeability of language in human communication and the potential for paintings to act as images open to interpretation. In this vein, we can explore a step further: if a printed painting is not a painting, then what is it? And what is its relationship to language?

I am inclined to see languages and images as conduits between different dimensions. Indeed, “I” am among them in these liminal spaces, because I am using mediums, and at the same time, I am a kind of medium (in the sense that a medium is “an intermediary thing that can make other things possible”). I see “my” multifaceted interactions with these artworks as junctures that lead into a different dimension of life and space-time. My countless circlings, sallies, flailings and absorptions have produced a text that now itself exists in a liminal state, awaiting the readers that will navigate and traverse it.

Viewer Situation #1 – The Stele with No Inscription

If the stele were not blank, this scene would not linger so profoundly in my mind. As it is, this visual experience opens up a realm of possibilities reminiscent of Borges’ Book of Sand. For example: the stele inscription, traditionally a vessel of weighty meaning and historical value, has been “wiped away,” creating “negative space,” and “rebirthing” a new significance that wavers between commemoration and void; or perhaps the imposing stele has been transformed into a mirror-like surface that turns the viewer’s gaze to reflect upon herself; or perhaps the erasure of its historical text leads to a renewed sense of lightness, in which the stele becomes simply a shield against the wind amid the rocks and trees, one that seems to make more accessible the distant lands beyond the horizon.

I see a metaphorical situation between this scene and the experience of encountering the paintings of Yu Han: the viewer expects to meet with an artwork that possesses meaning, but that artwork may, like the stele with no inscription, suspend us within a vacuum where meaning is inscrutable.

The stele has no inscription, but as an object standing upright in the wilderness, it transmits a certain message between the heavens and the earth, producing a different kind of significance. The facial expressions of the spectators within the painting are hidden, which seems to suggest that the deciphering of this significance—and the process of seeking it—may indeed transcend the realm of individual happiness or sadness.

Viewer Situation #2 – Who is Omnipresent?

Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia ego, 1638, oil on cloth, 85 × 121 cm, Louvre Museum.

If there were an inscription on the stele, perhaps it would recall the words “Et in Arcadia ego,” the words on a tombstone in Nicolas Poussin’s painting of that name, from another time and place, which also portrays the reading of words engraved in stone.

“Et in Arcadia ego — Even in Arcadia, there am I.”

In the bright light of day, the epigraph on the tomb is clearly visible. In Arcadia, that otherworldly Utopia of ancient Greek myth, can a group of carefree youths read and understand the true meaning of this line?

Like the shepherds in the painting, we viewers surely must debate who the “I” is in the epigraph. Is it the God of Death? Or perhaps the concept of separation? Though there are words on the tablet, their meaning is shrouded in uncertainty. Now let us imagine that the tombstone were blank, leaving only its emptiness to contemplate. Would silence, and the absence of writing, produce a similar semantic significance as the writing does?

This seems to be another metaphorical condition of the experience of encountering Yu Han’s paintings: whether the markings on the canvas are rich or paltry in their apparent significance, they simultaneously suggest a dearth of meaning. Meaning both is omnipresent and fleeting.

From Reading the Memorial Stele to Et in Arcadia ego, we advance from an individual viewing from a distance (the relationship between the viewer and the stele in the former) to a group engaged in discussion (the relationship between the group of viewers and the tombstone in the latter). We approach to the point of “touching” the artworks—or, more accurately, the particular substance of the artworks begins to “touch” us.

Eye Contact

From a macro perspective of time and the origins of life, humans are a relatively up-and-coming entity on this earth. Without a doubt, the planet was filled with living creatures long before humans appeared. I suspect that the first time any animal met eyes with a human was a particular experience that lodged deeply in its memory. In Why Look at Animals, John Berger wrote:

Yet the animal—even if domesticated—can also surprise the man. The man too is looking across a similar, but not identical, abyss of non-comprehension […] he is always looking across ignorance and fear. And so, when he is being seen by the animal, he is being seen as his surroundings are being seen. His recognition of this is what makes the look of the animal familiar. And yet the animal is distinct, and can never be confused with man. Thus, a power is ascribed to the animal, comparable with human power but never coinciding with it. The animal has secrets which, unlike the secrets of caves, mountains, seas, are specifically addressed to man.[4]

A clear point of distinction between humans and animals is that humans use language to communicate, and see other users of language as their brethren, whereas animals do not use language. They communicate using gestures, expressions, sounds, and silence incomprehensible to humans; they have close or fraught relationships with humans; and they are objects that we subject to our projections. The richly dramatic element of this relationship is that as humans grow evermore fond of animals, we also feel an increasingly inescapable guilt over the process of evolution, for it is the evolution of humans that is contributing to various degrees of ecological catastrophe. And it was when Homo sapiens reached the apex of the food chain about one million years ago that he began to imagine a collective identity where none previously existed.[5]

Perhaps there is nothing surprising about this. After all, humankind’s first subject in its cave murals was not itself, but rather, other animals. The human self-image only appeared later. In the cosmology of those prehistoric times, humankind saw animals as possessive of cosmic powers. Life and consciousness were not phenomena exclusive to humans, and “consequently, [animals] were not to be slighted; they were not seen as a lower order of existence or as amusing lesser versions of humans.”[6] Animals themselves were a medium through which humans communicated with the natural world. As a non-verbal means of communication, art inevitably became a means for humans to attempt to communicate with the universe as well as the animals that represented aspects of the universe’s powers.

Ineffable Forms: A Narrative of Emptiness

Though Yu Han feels time slows through the process of repetition, he has never departed from the mundane. He practices his temporal alchemy as his everyday work, and the familiar yet strange rabbits that appear in his paintings are not a subject material that he sought out consciously. Rather, they’re a subject that came to him, through companionship, by chance.

His affinity with rabbits began when a friend gave him one as a gift. Seeing rabbits on a daily basis, he began to feel increasingly familiar with the species. When their eyes met, it occurred to him that by looking at the rabbit, he was looking back at himself. What would happen if he tried to see the rabbit not with a human’s gaze, but with a rabbit’s gaze? “I thought that if I could look with the eyes of a rabbit, I could see another rabbit as like a lion. That’s something I could never see with a human’s perspective.”[7]

If we compare the artist’s creative practice to a flowing river—and see artworks from different moments as links between past and future—then his new series of paintings “In the Name of the Rabbit” can be easily traced back to the artist’s previous “Rabbit Portrait” series, perhaps helping us to step into this river of time. In an incisive analysis of the “Rabbit Portraits” and related works from the same period, the German scholar Beate Reifenscheid wrote, “Shao Fan transforms the visages and postures of the animals into monumental forms. Age and wisdom endow them with an extraordinary air of the eternal. This allows them to seem both comprehensible and also unreachably distant.”[8] In this essay, Reifenscheid applies her analysis of the techniques of imagery in Albrecht Dürer’s famous Self-Portrait with Fur Collar to Shao Fan’s animal portraits. She points out the diversity of his approaches to a single subject within the context of Chinese painting traditions and the ideas of Western portraiture. The resulting transformations are not simple portraits; rather, they represent the virtually eternal visage of a living entity and its existence within this mortal life.

In the creative process of “In the Name of the Rabbit,” the artist switched completely to ink on xuan paper for his medium. Moreover, the imagery in this series reveals an evolution into a space of greater intensity. The rabbit image is still discernable in these paintings, but when one locks eyes with these creatures, the concept of what they are gradually dissipates, as do all barriers to unfiltered perception. The sense of confrontation gradually dissolves in this meeting of eyes as we viewers enter a dimension of communal consciousness with the artworks. I call it a “dimension” because this feeling of communal space and time cannot be lightly named. The intuitions of our perceptions are indescribable, and indeed, ineffable, and thus this communal dimension is no illusion. As viewers we are always on a journey, re-tracing the brushstrokes of the painting.

Exhibition view of Shao Fan: In the Name of the Rabbit, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2023.

When we further examine Yu Han’s interest in repetition, we see that it takes place not only within the picture plane of each painting (as a tree intuitively forms branches at natural time intervals), but also, in the relationship between the paintings. The artworks in the series “In the Name of the Rabbit” gradually unfold, inviting us into a temporal garden. As we weave our way through this space, blurred semantics and indeterminate auras lead us to feelings of ethereal lightness and shelter.

In this dimension of communal consciousness, we establish a mutual trust with the subjects of these artworks and a curiosity about the “other.” In this relationship of visual dialog, even the rabbit without eyes does not strike us as grotesque or irregular. On the contrary, we sense that it is using its entire body and mind to meet “our” gaze, and is engaging in dialog with us with every hair on its body. It seems to not need actual eyes, for its “inner sight” is its sole means of exploring that which is ineffable.

According to the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, there is no Rosetta Stone of meaning to decode existence within this world. If we see a painting as an unfamiliar world, then “the key is not to identify themes relating to this painting, or to reference the historical circumstances of its origins. The key is to focus one’s perceptions on the object itself: to gaze at and perceive this artwork according to the directives silently given by the marks of the brush on the canvas, and in this way, to follow these directives—with no need for language or reasoning—to form a conception of the painting in its rigorous and orderly entirety.”[9]

Even if we cannot fully understand that entirety, that need not dampen our interest in the world around us. On the contrary, this kind of experience can spur our sense of adventure: “to depart from the human experience and leap into a boundless, undefined realm that allows us to reflect back on human experience.”[10]

When we stand in front of the artworks in the series In the Name of the Rabbit, intuition tells us that the center of the tableau is the rabbit’s mouth: its respiration, inhaling and exhaling, offers a dialog that transcends human language. These breaths congeal into words one wishes to speak but must leave unsaid, reminding us of Piero della Francesca’s Madonna del Parto (1455-1456). In that painting, the Virgin Mary wears a poignant countenance of mixed emotions and forbearance. But the unseen center of the painting—the unborn child in her womb—is the core around which the narrative swirls. As viewers, we find ourselves at an inflection point between two worlds, immersed in the vast possibilities that the future holds.

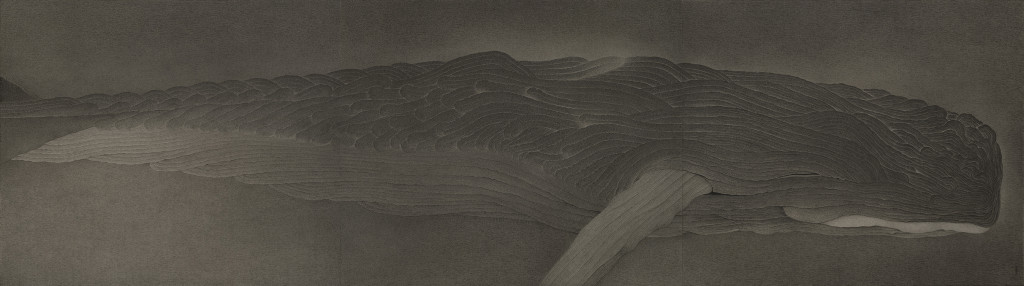

Ineffable Forms: Order within Chaos

The volume and topography of present times find expression in other recent works by Yu Han. In the painting In the Northern Ocean, we find an embodiment of another type of ineffable thing—could it be Kun, the giant mythical fish described by Zhuangzi in “Carefree Wandering?” Or some other indescribable creature, roaming through either the ocean or the sky (here, there seems to be no importance to differentiating between air and water molecules). It seems to come from another dimension, and yet it appears before us vividly and distinctly, as if drawn from the artist’s personal experience.

Shao Fan, Beiming (In the Northern Ocean) 0122 , 2022, ink on rice paper, three parts, 160 × 570 cm overall

The sense of space suggested in In the Northern Ocean itself recalls the discussion of big and small in “Carefree Wandering,” and the artist seems to engage in a dialog with that ancient and precocious text from another time and place. But the ineffable thing more directly corresponds to the shape of time—which to this day we are unable to capture—and the shape of the lives that we live.

Contemporary physics seeks to define “order within chaos”: the effects of objects, the organic structures of energy, matter and anti-matter. The force of any contradiction propagates within objects; energy gathers and seeks energy, rather than simply being consumed; otherwise, we have no way of explaining how a living thing as complexly structured as human beings could come to be in a place like our planet in this universe of increasing entropy.

Therefore, we can reference “self-organization,” this new scientific principle, to understand how order emerges from chaos […] chaos may be the ultimate state of matter, and at the end of time, the universe will surely have collapsed. But the Second Law of Thermodynamics absolutely does not state that this process occurs evenly across every moment and every part of space-time.[11]

In this nonhomogeneous world, in which all matter seeks equilibrium, contemporary physics reveals to us that no human is their own master, and mutual relationships give the myriad things their identities. The natural order of things can only appear and disappear within a dynamic chaos. Such is the foundation of “deterministic chaos,” which implies that no object or being can completely free itself of the relationships that define it. Whether it is social movements, biological evolution, or creative activities, the emergence of order within dynamic chaos resembles the blossoming of flowers in spring.

Exhibition view of Shao Fan: In the Name of the Rabbit, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2023.

Can one painter’s labor truly capture the movement of the cosmos and form images from that resonance? For Yu Han, this is a practice of exploring fundamental principles, learning from others, grinding and polishing, and ultimately, producing meditative observations in response. And perhaps, by communing with viewers who are exploring their own life experience, the artwork goes beyond meditative observation, forming instead a certain kind of redemption (in the temporal rather than the religious sense of the word). Just as those early cave murals opened for humankind a passageway into another world: a place of rebirth.

The whale-shaped creature in In the Northern Ocean does not resemble some sort of destructive sea monster or Leviathan, nor is it the mythical white whale from Moby Dick. There is no absolute negative force, and the accumulated layers of ink neither affirm nor negate their predecessors. Rather, they merge together at opportune junctures, thereby producing a shape that corresponds to that of a whale: a vision somewhere between affirmation and negation. As the artist gives himself over to the guidance of powers beyond his control, we follow him on a winding journey to a secluded place. Together, we probe the existence of alternate dimensions, in which the painting itself becomes the perch of the ineffable.

When Paintings Become Places

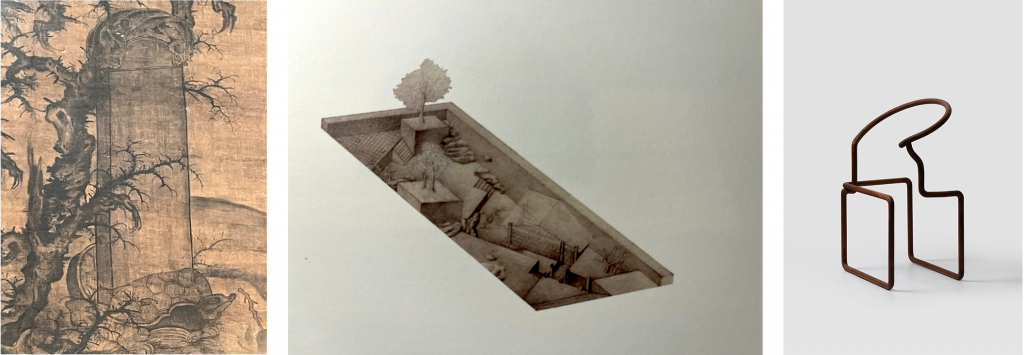

(Left) Li Cheng and Wang Xiao, Reading the Memorial Stele, Northern Song Dynasty (detail)

(Middle) Shao Fan, Mi Garden, 2008, Royal Horticultural Society, London

(Right) Shao Fan, Ring, 2013, walnut wood, 98 × 62 × 48 cm

Yu Han once built a sunken Chinese garden titled Mi Garden at the Royal Horticultural Society in London. This temporary garden was partially submerged beneath the earth’s surface, creating the effect of a “ruins.” The space was both dug into the ground and open to the skies above, temporarily suspending the concept of the earth’s surface. As the garden’s name implied—mi (觅) means “to seek”—the installation seemed to draw attention to that which is hidden. If we return to the tableau of Reading the Memorial Stele and carefully examine the stele itself, we discover that it is devoid not only of writing, but also of any trace of damage or weathering. The desolate air of the scene is in fact generated by the juxtaposition of the flawless stele with the rugged trees and strange rocks that surround it: an “undamaged ruin.” This rich artistic conception, laden with contradiction, reflects the thought-provoking Chinese cultural traditions of nostalgia[12] and looking to the past, which strikes a distant correspondence with the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s discussion of the “contemporary”: “In modern and recent times, the only contemporary people are those who are sensitive to ancient symbols and relics.” Agamben continued:

A contemporary person is not only someone who perceives the darkness of the present and also the light she is fated to never reach, but also someone who divides and occupies time, someone who can manipulate time and make connections between the present and other eras. She can read history in unexpected ways and cite it according to a kind of necessity. This kind of necessity, in any case, does not come from her will, but rather comes from that what she must do in order to respond to a certain sense of urgency.[13]

Compared to the weight of history, a stele is a relatively light material. If we were to imagine a different setting for a forest of steles (stele forest [beilin; 碑林] is the Chinese term for a group of inscribed stone slabs)—perhaps a more vast time and space, devoid of gravity—then each stele would resemble a sheet of paper, adrift on cosmic winds. The sacredness of a stele forest, unlike that of a church or temple, comes from its historical character. In Chinese culture, there is a sacrosanct relationship between history and metaphysics. In Chinese poetry and painting, the human and the divine always come together in relics and ruins: places that evoke the past and conjure homeward journeys. These places contain the balanced contradictions between presence and absence, having and not having, flourishing and withering, rising and declining, substance and void, the present and the past. Such places where complementary opposites interact have the potential to become sites of contemplation and shelter.

Perhaps Yu Han intended these paintings to provide “sites of communal contemplation” to which all individuals bring their own lived experiences. Unlike specific historical locations, these sites contain a void at their center, a certain detachment, which creates a singular instant in which artistic perception can occur. In this way does Ring, the round-backed armchair created by the artist, contain an emptiness at its center that anticipates a novel relationship to the body: a relationship in which the body’s overloaded physical memory can be purged. In such a relationship with art, our presence in the moment of mutual encounter creates an opportunity for us to form anew the relationships between our bodies, minds, and souls.

Exhibition view of Shao Fan: In the Name of the Rabbit, Mirrored Gardens, Space 1, Space 2, Guangzhou, 2023.

Afterword

When we lock gazes with an ineffable object, we are led to ponder the drift of humankind upon the seas of time; the fragility of geological transformations; the limits of an infinite universe. We may even imagine the ultimate fate of humankind amid the cosmos. Do these contemplations leave us any more at ease?

From where she lies she sees Venus rise. On. From where she lies when the skies are clear she sees Venus rise followed by the sun. Then she rails at the source of all life. On. At evening when the skies are clear she savors its star’s revenge. At the other window. Rigid upright on her old chair. It emerges from out the last rays and sinking ever brighter is engulfed in its turn.[14]

In this moment, only “this” remains. She, one member of humankind, unable to escape the principles of earth’s gravity, gazes at the stars, “as if transformed into a stone.” This, her, a once-proud energy—a legacy passed through human genes—gradually vanishing into the heat death of her individual universe, melting into the seas of nature’s molecules, taking with her all of the laughter and arguments and love affairs of her past.

This is not a tragedy, nor is it a comedy. In a certain sense, it approaches the model of the cosmos built upon the foundation of human imagination: everything eventually ends in heat death. Prior to that final moment, humankind’s laughter and chagrin will endure for many years, before ultimately dissolving along with this celestial body. Or perhaps the very intensity of humankind’s unthinking love and hate will cause the arrow of time to once again change its speed and direction. All along, what will remain unexplained is this: that person in motion who seems to be blind, possessor of an inevitable material momentum—how can she miraculously sublimate into a symphony of the spirit, rising above all joy and sorrow?

Within this limited human life, is an unlimited destiny an unbearable burden? If we do not base the value of humans (a limited entity) on that which is unlimited (the spirit or some sort of telos), then how do we assess the value of our existence? How do we candidly face the facts of life and death?

Our current understanding of humans—defined by our understandings of life, labor, and language—is one born in the modern age and presently facing its own demise. But might there be some sort of “ultimate experience” that transcends explanation and knowledge, a timeless passageway that connects the finite to the infinite?

This kind of ultimate experience has appeared in various guises throughout human history. Samuel Beckett’s “conscious man” pushes toward the extreme limits of language, as if humankind could once more affirm its existence before vanishing. But there are no correct words for this affirmation, just as there is no inscription on the stele in Reading the Memorial Stele.

Beneath the vast and boundless skies, humans seem to struggle evermore to find expression. Each word we speak is like a distant star, drifting ever farther away, a faint glimmer barely visible to the naked eye, and the dark night occupies ever more of each day. “Here, we once again encounter the earliest finite subject. But this kind of finite subject […] appears on a more basic level: this is the inescapable relationship between human existence and time.”[15]

In the last one hundred years, the artist has witnessed the besieging of humankind, the “death of the author.” She is left no choice but to rush about the boundless wasteland, to directly face the emptiness of the world, and to draw on art to explore the special order of things: those material and spiritual entities that cannot be ruled by laws. How can their intrinsic quality and space be expressed?

the silence

of nature

within.

the power within.

the power

without.

the path is whatever passes—

no end in itself.[16]

( This article is an abbreviated version of the essay with the same title, published with permission of the author.)

Essay: Hu Fang.

Courtesy of Vitamin Creative Space. © Vitamin, 2023.

All works of art by Shao Fan © the Artist, 2023.

__________________

[1] Gary Snyder, “Source,” in Turtle Island: Poems of Gary Snyder, New Directions, New York City, 1974, p. 26.

[2] The subject of this essay, the artist Shao Fan, uses the art name Yu Han. An “art name” (号), an archaic tradition from China’s past, subtly expresses an artist’s alternative self-image. This alias may more closely represent the relationship between works of art and the creative individual implied behind them. For this reason, this text refers to the artist Shao Fan by his art name, Yu Han.

[3] I know little about Étienne Gilson, the French philosopher who wrote these words, but I suppose that his lifelong study of medieval theology and Thomas Aquinas led him to deeply appreciate the impossibility of translating art into language, a task as futile as verbally articulating the soul.

[4] John Berger, Why Look at Animals?, Penguin Books, London, 2009, p. 14.

[5] See Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, cited in Chinese, Lin Junhong trans., CITIC Press Group, Beijing, 2017, p. 69-71.

[6] Gilbert Simondon, Deux leçons sur l’animal et l’homme, cited in the Chinese, Song Dechao trans., Guangxi People’s Press, Nanning, 2021, p. 46.

[7] In conversation with the author, 14 October 2022.

[8] Beate Reifenscheid: “Shao Fan—From Portrait to Countenance,” collected in Yu Han 1984-2018, Eastern Publishing Co, Beijing, 2018, p. 9.

[9] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Causeries 1948, cited in the Chinese, Wang Shisheng, Zhou Ziyue trans., Jiangsu People’s Press, Nanjing, 2019, p. 80-81.

[10] Byung-Chul Han, Die Austreibung des Anderen, cited in the Chinese, Wu Qiong trans., CITIC Press Group, Beijing, 2019, p. 92.

[11] Peter Coveny and Roger Highfield, The Arrow of Time, cited in the Chinese, Jiang Tao and Xiang Shouping trans., Hunan Science and Technology Press, Changsha, 1994, p. 15.

[12] On the expression of nostalgia through recurring visual themes, see Wu Hung, “A Story of Ruins—Presence and Absence in Chinese Art and Visual Culture,” in bei yu kushu: huaigu de shihua, Xiao Tie trans., Shanghai People’s Press, Shanghai, p. 32-56.

[13] Giorgio Agamben, Nudita, cited in the Chinese, Huang Xiaowu trans., Peking University Press, Beijing, 2017, p. 34-35.

[14] Samuel Beckett, “Mal vu mal dit,” cited in the Chinese, Xu Zhongxian trans., collected in Beikete xuante xuan ji (5): kan bu qing dao bu ming, Hunan Literature & Art Press, Changsha, 2006, p. 197-198.

[15] Liu Beicheng, Fuke sixiang xiaoxiang (The Portrait of Foucault), Beijing Normal University Press, Beijing, 1995, p. 135.

[16] Gary Snyder, “Without,” in Turtle Island: Poems of Gary Snyder, New Directions, New York City, 1974, p. 6.