Notes on Wang Yin

Traveling on and on,

Living apart from you.

Separated by a thousand miles,

At opposite ends of the earth.

The road is long and obstructed.

Who knows if we’ll meet again?

The horsemen of the North need the wind,

The birds of the South need tree branches.

Our last meeting was long ago.

My clothes hang loose on my body.

Clouds float beneath the white sun.

The wanderer looks not over her shoulder.

Thinking on you makes me older.

At once, it seems late in months and years.

Let us not revisit our past parting.

Please remember to eat well! [1]

At the break of dawn, when poetry and narrative have yet to draw apart, the mists of the cycles of the cosmos preserve the original emotional relationship between man and the world. This is how humankind proceeds: naturally producing narratives and expressions of emotion, rich in restraint.

As channels connecting individuals to the outside world, poetry and narrative jointly reveal the true face of the world’s existence.

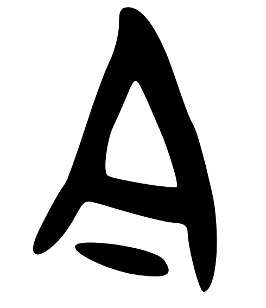

At this early hour, perhaps “to paint” and “to write” have not yet been fully separated, nor have “realism” and “expressionism.” All expression originates in needs that belong to the relationship between man and the world. Depiction and shelter are fused into one.

——

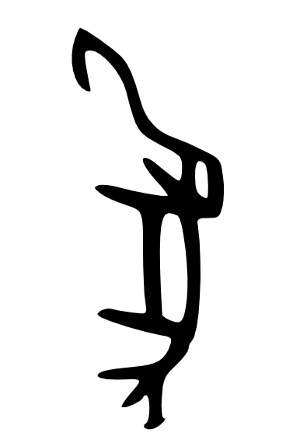

The philosopher Zhao Tingyang shared with Wang Yin the origins of the character 今 (jīn–now): “It’s the sound of a bell (铃). When the clapper strikes the bell, the sound it makes is jīn.”

Jīn: A warning sound. An instant.

In his paintings, Wang Yin seems to respond to a certain aspect of contemporaneity: when the bell of the present moment sounds, it contains all of the past, and is also a portent of the future. It warns: we must face everything. In the words of the Grand Historian Sima Qian, “one must understand all the transformations from ancient times until now (今).”

This sound may be the sound of our actions, or of our thoughts, or of the reverberations of every ramification of all that we’ve done.

——

If our understanding of the “jīn” sound of the bell can be extended to performance art, then perhaps we can shed new light on the traditions of Chinese theater. The ostensibly stylized performance of Beijing opera inspired Brecht’s reflections on the “distancing effect,” as well as Eisenstein’s “montage theory.” Every movement in an opera performance is an insight into (and refinement of) human nature. Does it not reflect the gleam of light cast by Nineteen Old Poems on the value of human existence?

The issue of performativity provides a useful reference point when we question how the artist can “perform without performing” within the practice of painting. If the actors can “perform without performing” by maintaining distance from their role, effectively expressing their objects and the performance itself, then the conscious or unconscious distance created through the painting process must also be an exploration and interrogation of the artist’s own positioning. In this way, the painting process ceaselessly penetrates deeply into life while also stepping outside of it to observe.

When I consider stage photos of Cheng Yanqiu and Tan Xinpei next to certain paintings by Wang Yin, words come to mind such as “proprioception.” At the same time, I also reflect on the twentieth-century theater practices of the West, such as Grotowski’s theory of “poor theater,” which help me understand another aspect of Wang Yin’s painting: the stripping off of all excess.

In fact, Wang Yin’s paintings always shun portrayals of specific experience. When we face such paintings, we are inevitably moved in a complex way. We seek to decipher them, but all of our insights are ultimately simplifications and prejudices of meaning. We can perceive the phases of Wang Yin’s creative practice as a process of subtracting excess significance. Laozi reminds us: “To learn, increase daily; to follow the Way, decrease daily.” In this process of exploration, the relationships between the techniques and the “Way” of painting are continually transforming, and these transformations produce all varieties of refinements, condensations, and layers of perception. This journey allows us to glimpse a kind of experience available only through alienation, in order to reach the deepest, most universal emotional crystallizations of human nature.

——

It seems to me that the images in Wang Yin’s recent paintings recall the sound of bells at daybreak. Here is the dawn that the night watchman awaits, the coalescence of deep feelings–feelings both familiar and foreign, feelings that we may even have forgotten. Because they respond to the different life experiences of each person who experiences them, they trigger different rational and emotional responses. Wang Yin’s method of reaching people through painting relies on the humble power of painting itself: the power of art’s potential, possibly akin to nature, complex and yet simple.

——

It is said that the character “象Xiàng”(appearance) dates back to prehistory, when the plains of northern China were warmer than today, and elephants (大象) lived in the Yellow River basin. Due to changes in the climate, the elephants migrated south, leaving their namesake character behind them.

Through marks and vestiges, we perceive appearances: we trace these marks back to that which we once possessed but has since disappeared.

In comparison to his focus in earlier work on “regional voices,” Wang Yin’s recent work compels us to wonder: is it possible for contemporary painting practices to respond to something universally shared by paintings? Something that cannot be seen or touched, but can only be sensed through immersion in painting practices? Can we suppose that this something is a common consciousness, intrinsic to painting?

For example, can we not perceive a certain sensibility shared across time and space between the paintings of Cézanne and Dong Qichang? An uncanny resonance between the shapes and lines of the Kizil cave murals and the paintings of the early Renaissance?

Something universal, something that cannot be seen, but certainly exists.

Something condensed and essential.

Something like“象Xiàng.”

The common experience of painting is necessarily related to the common experience of human life. Is art, in a certain sense, a requisite component of the continuation of human life? I am reminded of something Wang Yin once said: “Painting is a way of organizing life anew.”

——

“象Xiàng”(appearance) offers a useful reference when we consider the nature of the “common experience” in question. For example, the image of 渔樵 (yúqiáo–the woodsman/fisherman, one in whom thought and action are united) has existed for thousands of years, as a motif in Chinese literati painting but also in various other guises throughout Chinese society. When we seek the internal essence of the yúqiáo image, we see how it relates to other images with completely different external forms. For example, Walter Benjamin writes of the flâneur (loafer) of the modern metropolis, who strolls through the urban jungle, generating ideas. Another example: Samuel Beckett writes of the self-exiled refugee, another motif in dialog with the yúqiáo:

When I am abroad in the morning I go to meet the sun, and in the evening, when I am abroad, I follow it […] Living souls, you will see how alike they are. [2]

Perhaps it is through this manner of “action through inaction” that the practice of art fuels a primeval labor: one that restores the integrity of existence and cuts through to its underlying images; one that lies latent beneath the surface of tranquility and accompanies the exploration of eternity.

——

I discover that the evolution of this work is always approaching the characteristics of something like “survival.” This is what I have lately perceived. [3]

How does one survive through art? What is the art of survival? Could it be that one day, due to our dalliances in painting, a certain expression, pattern, pointillist texture, a heavy brushstroke, or a familiar and yet foreign form will unexpectedly deliver to us a secret and complex emotional experience that opens passageways through time, and restores to us our imagination, stifled by the epoch, as well as our “intrinsic reason, obstructed by crude ideology and overgrown concepts?” [4]

Perhaps this fleeting feeling of survival is one that contains all that has passed while continuing to transform. If so, how can it penetrate the limitations of painting? In fact, it is these limitations that allow painting, as a medium, to express such ephemeral sensations.

I sense that Wang Yin thus cherishes the gift of time, his only foundation, such that all he retains is the paintbrush in his hand.

——

The survivor is no longer restricted and entangled by the explicit guidance of his environment. All that remains is the individual, radiating a versatility that fuels our imaginations, or unveiling a distinctive assemblage–a kind of conjoining. Correspondingly, painting becomes multifarious, implying the anticipation of future transformation: one day, due to the slightest change in texture or hue, they will move toward a new era, toward re-formation–and rebirth–on the remaining sense of survival.

Amid this sobering silence, the scenes within the paintings lead us back to the solemnity and fragility of humanity’s childhood, a time before the amorphous sincerity of human nature was transformed by our institutions into sophisticated expressions. These paintings do not retrieve or reproduce specific expressions. Rather, they explore how our expressions might be returned to forms of innocence, and how such forms might become a “setting” unconstrained by the times: a testament to that which is natural and free within humanity, even today.

Hu Fang

Texts©2021Authors

All works of art by Wang Yin©the Artist

Photo: Wen Peng

Courtesy of the Artist and Vitamin Creative Space

[1] “Xing xing chong xing xing,” from Gushi shijiu shou (Nineteen Old Poems).

[2] “The Expelled,” collected in Samuel Beckett, Four Stories, Zou Yan, Tu Weiqun, Zeng Xiaoyang trans., Hunan Arts and Literature Press, p. 22.

[3] Wang Yin in conversation with the author, October 2020.

[4] Wang Yin interview, “Better to Tell the Old than Make the New,” 2009.

》Notes on Wang Yin.PDF